The Saunder’s Park neighborhood of Minneapolis once stood on the northeast section of the cemetery (where Hubert Humphrey is buried today). The 1903 map below shows the Saunder’s Park neighborhood in relationship to Lakewood. What was Saunder’s Park? Was it a real neighborhood? Did it always belong to the cemetery? And what happened to the buildings?

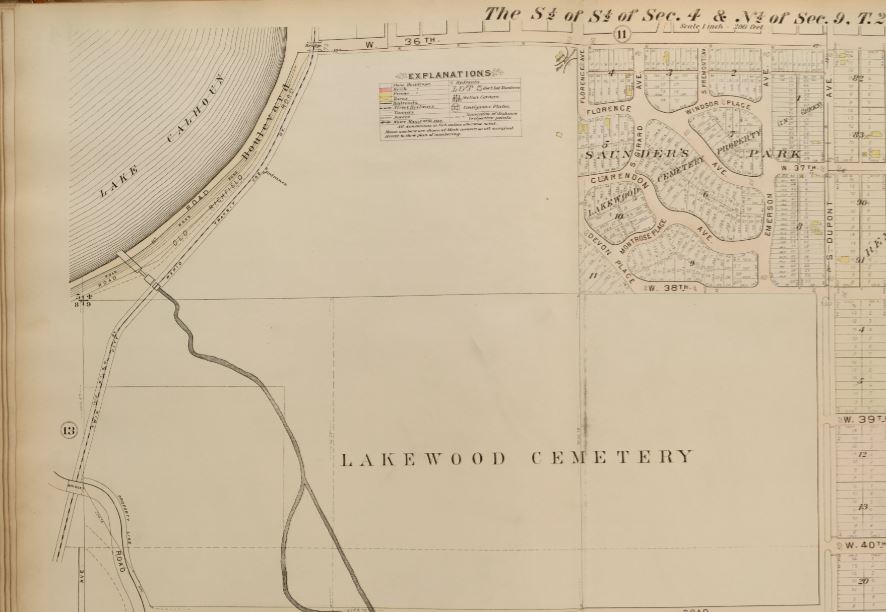

A 1903 map of Lakewood Cemetery and the Saunder’s Park Neighborhood. Source: University of Minnesota

Saunder’s Park tells a unique story. It’s a story of cemetery expansion in the rapidly growing city of early Minneapolis—and, interestingly, it’s also a story of how Lakewood became a hub for horticulture.

Lakewood Cemetery was founded as a nonprofit association in 1871. The following year, it opened to the public in a grand ceremony. At this time, Minneapolis boasted a population of around 13,000 and the city stretched as far south as Franklin Avenue. A handful of private, religious, or municipal graveyards existed within the city limits, but nothing so large or enmeshed in nature as Lakewood. The original cemetery occupied just 130 acres (compared to 250+ acres today). At the time, this amount of burial land was sufficient for a city of this size.

But the city grew very quickly. In 1884, long standing Lakewood Superintendent A. B. Barton stepped down and was replaced by the reformer Ralph D. Cleveland (son of landscape architect Horace Cleveland). Though additional land was not immediately needed for burial, Cleveland foresaw that the cemetery would have to secure more land if they wanted to continue to provide a place of beauty, peace, and solace for future generations in the growing city of Minneapolis. It was under Cleveland that Lakewood expanded to its current size.

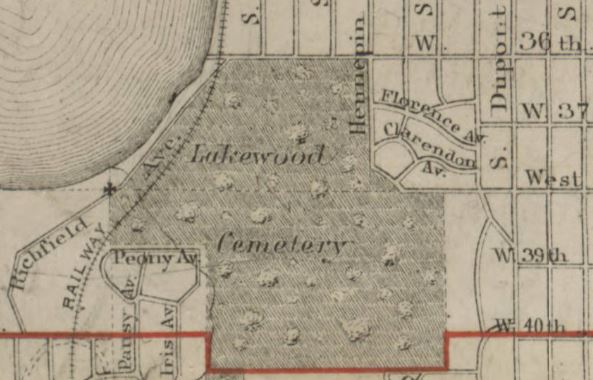

Lakewood Cemetery in 1885. Note that the cemetery had not yet expanded into the Saunder’s Park neighborhood, with streets like “Florence Av.” and “Clarendon Av.” Source: Hennepin County Library

With Lakewood’s western border already nearly touching Lake Calhoun (Bde Maka Ska), Lakewood looked to expand eastward. The Saunder’s Park neighborhood, pictured in the map above, was located in what is now the northeast corner of Lakewood Cemetery, bounded externally by 36th Street and King’s Highway.

In 1884, the Association’s board gave permission to the staff to move forward with purchasing a large portion of this neighborhood. The purchase went through in 1888. The next big expansion came in 1903, when the Association bought another 50 acres of Saunder’s Park neighborhood, which included 259 lots and 17 dwellings.

Saunder’s Park was a unique neighborhood. At a time when the growing city was arranged largely on a grid, Saunder’s Park featured small, winding roads. It was removed from the urban center—the trolley didn’t connect Lakewood to the rest of the city until 1895. In addition to its distance from the inner city, newspaper articles at the time noted that a local judge lived in the neighborhood. These facts suggest that the population of Saunder’s Park neighborhood was fairly well-to-do.

Most of the neighborhood’s lots were owned by a small number of prominent real estate owners (including Charles Loring and James J. Hill). This made the purchase of most of the neighborhood relatively easy for Lakewood Cemetery. (Lakewood already had a positive relationship with Charles Loring, who served as the first superintendent of the Minneapolis Park Board: in 1890, Lakewood donated 35 acres to the Park Board for the establishment of Lyndale Park and the Rose Garden.) Throughout this long acquisition process, most of the Saunder’s Park neighborhood residents willingly left their houses to allow for the expansion of the park-like cemetery. However some neighbors were more resistant to the change. In 1903, Lakewood attempted to purchase about 30 lots, owned by individuals. When some of the lot owners resisted the purchase, the cemetery received permission from a local court to use eminent domain to acquire the properties. The decision was set to be heard again at the state’s Supreme Court, but the Association instead negotiated sales that were agreeable to the Saunder’s Park residents.

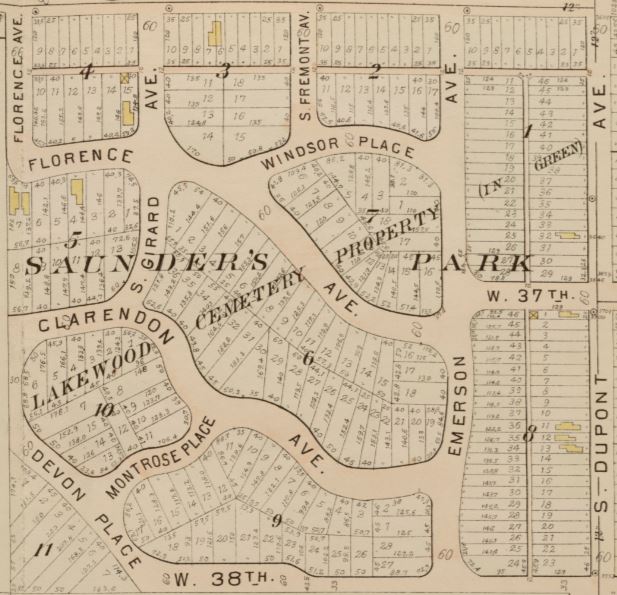

This 1903 map indicates that Lakewood Cemetery property is indicated in green. At this time, Lakewood had not yet secured all properties in Saunder’s Park. Source: Hennepin County Library

Most of the Saunder’s Park properties were dismantled when they came into Lakewood’s possession. Other properties were physically moved from the present site of the cemetery to nearby lots.

But one building was the exception to the rule. Hartman’s Greenhouse began operating 1886 in Saunder’s Park. This operation was one of many greenhouses near 36th Street, which had been nicknamed “Greenhouse Row.” When Lakewood expanded in 1888, this was one of the properties they acquired. Recognizing the potential for beautification that could result from having a greenhouse—as well as the business potential of the operation—Lakewood kept the greenhouse. Today that greenhouse is the oldest standing (and continuously operating!) greenhouse in the state.

A side view of one of Lakewood’s greenhouses, 1925. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

In the late 1800s, it was unusual even for large cemeteries like Lakewood to have their own greenhouse. In 1892, less than one quarter of Association of American Cemetery Superintendents member cemeteries nationwide operated their own greenhouse. Almost half of these greenhouse cemeteries were in Massachusetts. But Lakewood’s staff felt it would be beneficial for Lakewood and cemetery lot owners to have Lakewood’s floral and horticultural operations in house.

Shortly after Lakewood took over the greenhouse operations, they took their product outside the confines of the cemetery. Demand was high—which was good, because running a greenhouse in the late 1800s was expensive. Without thermostats, desired temperatures were reached through an involved balance of coal fire and ventilation. Employees worked to maintain the climate 24 hours each day. Additional staff had to be hired to deliver flowers, and horses and buggies were kept in the cemetery grounds to run deliveries to nearby cities.

The greenhouse operation blossomed. At its peak, Lakewood operated 6 greenhouses, each larger than a football field. They boasted a large, impressive floral showroom. By the 1920s, Lakewood was the largest floral wholesaler west of Chicago.

Inside the Lakewood Cemetery floral showroom, 1925. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

A few things slowed Lakewood’s greenhouse production. First, a 1924 lawsuit rightfully raised the issue that Lakewood, a nonprofit, had a competitive advantage in the floral industry, which was otherwise for-profit. In more recent history, the energy crisis of the 1970s forced many greenhouse operations across the country—including Lakewood—to scale back.

Today, Lakewood Cemetery boasts two large greenhouses. Lakewood is one of the country’s few remaining cemeteries with fully operational greenhouses on site. Over 100,000 flowers are planted each year.

Lakewood’s largest greenhouse today

Lakewood is a destination for its beautiful flowerbeds and arrangements. And it’s all thanks to the acquisition of Hartman’s Greenhouse in Saunder’s Park.

Learn more about our greenhouses then and now in this video!