In the 1890s, Charles Loring and Florence Barton may have seemed an unusual match. He was, after all, an “elderly” widower of 62 when they married on Thanksgiving Day in 1895. Charles’ first wife, Emily, had died of cancer in April the year before. At 44, Florence was 18 years younger, and may have been considered a “spinster” at a time when women were considered marriageable at 16.

Florence and Charles Loring in Riverside, California about 1914

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Charles and Florence had known each other for years. She was the only child of A.B. (Asa Bowers) Barton, the first superintendent of Lakewood Cemetery, and his wife Olive. After Lakewood was founded in 1871, Charles worked closely with Barton in creating it as a park-like cemetery, part of a trend to move burial grounds away from crowded inner cities.

The Loring and Barton families were close friends even before Lakewood was developed. They even shared living quarters for three months in 1867 when Charles, Emily and their son Albert moved in with the Bartons while they were having a new house built. Both families were part of a social network that included well-known names of the city’s past—Eastman, Morrison, Washburn and Brackett—and certainly attended many events and gatherings together.

Charles Loring

Source: Hennepin County Library

Businessman, Community Leader and “Father of Parks”

Charles, originally from Maine, arrived in Minneapolis in 1860 after a stint in Chicago as a wheat speculator and grain trader. He came to Minneapolis with Emily and their young son as tourists, essentially checking out the city and its potential. They liked what they saw and decided to stay. Like other newcomers, Charles immediately recognized the potential for industry presented by the Falls of St. Anthony.

After getting his bearings as manager of Dorilus Morrison’s supply store on Bridge Square at the foot of Hennepin Avenue, Charles became a partner in Loren Fletcher’s general store that specialized in supplies for lumbermen building sawmills at the Falls. The store was located across from City Hall.

As the business branched out into flour milling, Charles became active in city leadership. He joined the Minneapolis City Council in 1872. He began buying real estate. He became a member of the Minnesota Horticultural Society. In 1883, he was named the first president of the Board of Park Commissioners, and he remained in that role until 1890. He was not among Lakewood’s founding trustees in 1871 but joined the board in 1874 and immediately became its president for a three-year term.

Florence Loring

Source: Hennepin County Library

Talented and Artistic

By the time they married, Florence was a mature single woman with a full life. She studied music in Boston and enjoyed a successful career as a singer, performing regularly in Minneapolis. She formed the Cecilia Quartet — “four of the best female voices in Minneapolis” wrote the Minneapolis Tribune in 1877 — and organized a Thursday Musicale. (Perhaps she would approve of Lakewood’s “Music in the Chapel” concert series.) She was a convincing writer for causes she believed in and had an artistic bent. She had many friends. She was no lonely woman who’d given up on finding a husband.

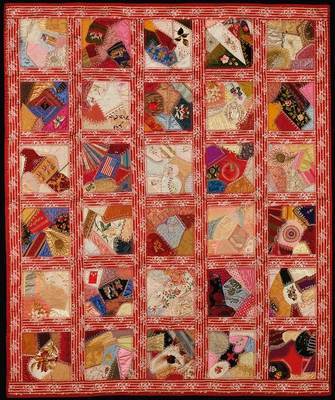

“Crazy quilt” created by Florence, completed in 1905

A “crazy quilt” is a visual biography of its maker. Each piece of Florence’s quilt refers to some aspect of her life, from her love of music, trees, birds and animals, to tributes to her friends and family. The quilt is owned by the Minneapolis Institute of Art. It is by now fragile and rarely displayed.

Kindred Spirits and a Surprise Wedding

It isn’t surprising that Charles turned to Florence after Emily’s death. The closeness of their families and their common interests combined to bring the two together. Both were interested in nature and horticulture, and both believed that parks were a necessity for residents of a fast-growing city. Charles’ interest was in the elements that created restful parks with graceful trees; Florence championed open spaces and playgrounds for the city’s children.

Charles and Florence planned to marry in a quiet way. In an era of lavish wedding parties, Charles and Florence chose a more discreet path, perhaps out of respect for the memory of Emily. In October 1895, Florence traveled to Chicago to prepare for her wedding, perhaps to buy a wardrobe suitable for a middle-age bride. On Thanksgiving Day, November 28, guests in Asa and Olive Barton’s home were surprised to also witness Charles and Florence’s wedding.

Partners in Community Service

In the years that followed, the couple became true partners in their dedication to the city they loved. Charles’ businesses had made him a wealthy man, despite economic ups and downs that at least once threatened his fortune. Through his lifetime he gave generously, starting in 1868 when he donated trees for the city’s first park, Murphy Square, on land given by Captain Edward Murphy. He was often called a “wonder worker with trees.” He chaired the planning committee for Minnehaha Park and went on to create the park and boulevard system that is still the pride of Minneapolis. In 1890, Minneapolis’ Central Park was renamed Loring Park in his honor. He was called, in his lifetime, “Father of the Parks.”

While Charles was busy establishing parks, Florence was advocating for “more space [for] unrestricted playgrounds for children.” In a letter to the Minneapolis Journal in 1900, she and a friend petitioned the park board for sandboxes and maypoles in Loring, Fairview and Riverside parks. (They were turned down due to lack of funds.) Florence belonged in her own name to the American Park and Outdoor Art Association.

In “City of Parks: The Story of Minneapolis Parks,” author David C. Smith wrote that Florence “became and remained Loring’s partner in philanthropy for the rest of his life.” They gave generously to Minneapolis charities such as the Children’s Home Society and The Minneapolis Relief Association. Florence donated funds for an animal shelter, which bore her name and stood until the 1960s.

After Florence’s parents Olive and Asa passed away in 1904 and 1905, the Lorings moved into the Barton’s house at 100 Clifton Avenue, where they’d had their wedding. (The neighborhood was becoming an area of magnificent homes including the Frederick W. Clifford mansion designed by Harry Wild Jones and featured in a recent Star Tribune article by architectural historian Larry Millett.)

In his book “Once There Were Castles” Millett describes the Barton house: a “fourteen-room Queen Anne finished in brick and patterned shingles . . .in the vanguard of a wave of mansion building that transformed Clifton between 1885 and 1910.” The home featured “a polygonal corner tower, a broad front porch, and numerous bays, balconies, gables and undulations.” No doubt it had plenty of room for entertaining the couples’ many friends.

The Barton-Loring house, 100 Clifton Avenue in Minneapolis

Source: Hennepin County Library

The Lorings remained in the Barton home until their deaths. In her will, Florence bequeathed the house to the Women’s Welfare League as a home for working girls and women who found themselves homeless in Minneapolis. She also provided a $50,000 endowment for its maintenance. Larry Millett notes that the League turned it into a convalescent home. The house was razed in the early 1960s for the Interstate 94 right-of-way.

The couple also enjoyed living part of the year in Riverside, California. Several years before they were married, Charles and Emily had established a winter home there. Florence joined him in supporting civic improvement projects in Riverside as well as Minneapolis. She donated money for an animal shelter there and helped fund a home for the local hospital’s student nurses.

The Lorings obviously enjoyed Riverside, but their hearts were loyal to Minneapolis. The city’s iconic Central Park, largely created by Charles, had been renamed Loring Park on December 20, 1890. Twenty-six years later, April 28, 1916, was designated Loring Day and nearly 100 tree planting ceremonies were held throughout the city to honor him as founder of the Minneapolis park system.

Tree planting in Loring Park, April 28, 1916

Source: Hennepin County Library

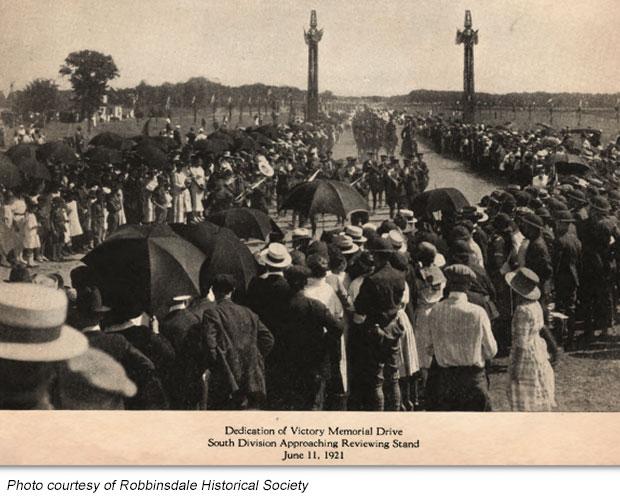

Charles’ last project was the creation of Victory Memorial Drive in North Minneapolis. He had it planted with 568 elm trees honoring fallen soldiers of World War I and established a fund of $50,000 to pay for the care and maintenance of those trees into the future. More than 30,000 spectators were present when it was dedicated on June 11, 1921.

Charles Loring died on March 18, 1922, the following year. Florence lived just two years longer; she died on July 29, 1924.

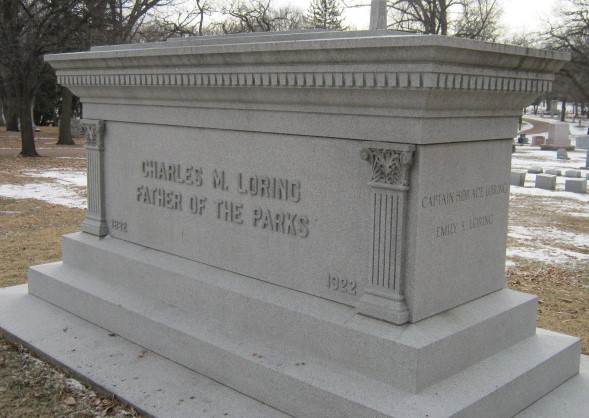

The Loring family monument at Lakewood Cemetery.

Theirs was a story of devotion to each other, their home city, its people and the environment in which they lived. They expressed this love with gifts of trees and music, and the parks, bike and walking paths we enjoy today.

Sources:

“City of Parks The Story of Minneapolis Parks” by David C. Smith

“Haven in the Heart of the City: The History of Lakewood Cemetery”

“Once There Were Castles” by Larry Millett

“Florence Barton Loring” blog post by David C. Smith January 13, 2011