If you’ve been following our blog throughout National Garden Month, you’ve learned about Lakewood’s greenhouse, garden, and horticultural history. Today we look at Lakewood’s connection to one of the nation’s most elaborate urban garden and recreation systems—the Minneapolis Park System.

Lakewood was founded in 1871, a full 12 years before the Minneapolis Park Board was incorporated. This means that Lakewood was, in essence, the first large-scale public greenspace in the city of Minneapolis. Lakewood’s early leadership was comprised of many early Minneapolis influencers with a bent toward landscape architecture and horticulture. In fact, many notable figures who went on to be instrumental in founding the park system got their start at Lakewood Cemetery. Among these mutual leaders are such names as Charles Loring, Thomas Lowry, Horace Cleveland, Harry Wild Jones, and more.

The first park?

Before we get to the shared leadership of Lakewood and the early Minneapolis Park Board, let’s address the issue of the “first park.” To say that Lakewood was the city’s first park isn’t completely accurate. In 1857, the same year that New York held a competition to design Central Park, early settler Edward Murphy donated a piece of land to the city to create Minneapolis’s first city-owned park. Born in 1828, this Irish-American pioneer moved to the frontier town of St. Anthony (now Northeast Minneapolis) in 1850. Shortly thereafter, he became one of the early settlers on the West Bank of the Mississippi. By 1873, the city had not developed his park, so Murphy took it upon himself to plant trees, create paths, and build fences. Today Murphy Square is the main square for Augsburg College.

Murphy Park in 1905. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Lakewood and the Park Board: Shared Leadership

On August 7, 1871, Minneapolis mayor Dorilus Morrison summoned a group of 14 Minneapolis businessmen to discuss the founding of a nonprofit, garden-style cemetery. The city of Minneapolis, which then had a population of 13,000, was growing rapidly, and these leaders wanted to be certain that residents had a peaceful space within which to honor their deceased loved ones. Together these leaders decided to develop the region’s first park-like cemetery, with winding roads, undulating hills, and plenty of plants and trees. Later that year they purchased the land for the original, smaller Lakewood Cemetery (now the northwest quadrant of the grounds) from settler William S. King.

Among these original founding members of the Lakewood Cemetery Association were three businessmen who would go on to be instrumental in the founding of the Park Board: Charles Loring, George Brackett, and Thomas Lowry.

Charles Loring

Charles Loring’s grave at Lakewood Cemetery clearly spells out the well-earned title by which Minneapolitans knew him. “Charles M. Loring: Father of the Parks.”

Charles M. Loring in 1900. Source: MNopedia

Loring served as the first president of the Park Board. He is largely credited with purchasing much of the city’s lakes and shorelines for parks. But before Loring became the Father of the Parks, he was instrumental in Lakewood’s founding. As a Lakewood founder and board member, Loring had a major influence on Lakewood’s early horticultural designs. With a deep passion for trees and flowers, he was heavily involved in the local floral industry, even hosting the city’s first flower show. Lakewood sent him (and other early cemetery leaders) to national American Association of Cemetery Superintendents conferences, where he learned and shared information about which trees and flowers performed well in Northern climates. (Note that this was before USDA hardiness zone maps, or the widespread existence of conservatories!)

The grave of Charles Loring at Lakewood, which reads “Father of the Parks”

There are multiple stories of how the idea for Lakewood first came to be. But one such story is that it was actually Loring who had the idea for the space. Unfortunately, somber circumstance led Loring to envision a place of memorial solace and beauty in the city. In 1863, Loring’s infant daughter died. At this time Minneapolis’s only public graveyard was Layman’s Cemetery on Lake Street, which was already overcrowded from 10 years of burials from a rapidly growing population. Years later, Loring wrote a letter to fellow Lakewood founder and Park Board member George Brackett. In this letter, he told Brackett that it was while burying his infant daughter in this overcrowded space that he made a promise to build a larger, park-like cemetery. (Learn more about Charles Loring and his wife Florence.)

George Brackett

When Charles Loring wrote that letter to George Brackett, he wrote to a trusted friend and colleague. Having established himself as a successful businessman and entrepreneur by the 1870s, Brackett was one of those businessmen summoned by Mayor Dorilus Morrison to establish Lakewood Cemetery. Loring and Brackett worked closely in the early days of Lakewood. They also worked closely after the Park Board was founded in 1883. Brackett was one of the early members of the Park Board, where Loring served as the first president.

George Brackett in 1907. Source: Wikimedia

In addition to making a fortune in groceries, milling, lumber, railroads, and real estate, Brackett also served as the sixth mayor of Minneapolis. Born in Maine in 1836, he moved westward until he settled in Minneapolis at age 20. He is the namesake of Lake Minnetonka’s Brackett Point (where he lived) and Minneapolis’s Brackett Park. Brackett remained adventurous until his final years. Already in his 60s, he endeavored to Alaska with his son in the 1890s to help develop a proposed shipping road. He returned to Minneapolis in 1905, and passed away in 1921.

Thomas Lowry

Another one of Morrison’s picks for city-savvy cemetery founders was Thomas Lowry. Lowry had arrived in Minneapolis with a law degree just a few years earlier in 1867 (the same year Minneapolis became a city). But Lowry found that the small frontier city presented little opportunity to practice law. Instead, he focused his efforts and investments in real estate. Within a few years, he had made a small fortune in real estate—and this fortune would only continue to grow.

Thomas Lowry in 1902. Source: Wikimedia

But Lowry brought more than a thorough understanding of real estate to the cemetery planning group. Lowry was a philanthropist and advocate for public services like parks and libraries. And Lowry had another connection to Lakewood—in 1870 he married Beatrice Goodrich, the daughter of abolitionist and medical doctor Calvin Goodrich, who served as Lakewood’s first president.

After working to establish Lakewood, Lowry went on to be an early member of the Minneapolis Park Board. He personally donated a significant amount of land for the development of parks. Thomas Lowry Park is named in his honor.

Lakewood Donates Land to the Park Board

Lakewood’s long ties to the Park Board brought many benefits to the park system. Two notable Minneapolis Park spaces were originally owned by Lakewood Cemetery, and were gifted to the Park Board.

In 1890, Lakewood donated 35 acres off the cemetery’s south end to the Minneapolis Park Board. In 1908, the Board opened Lyndale Park on this and surrounding land. In 1946, they added the remarkable Minneapolis Rose Garden to this donated land. Today, the Rose Garden can have as many as 60,000 blooms across 250 species of roses each season. The Rose Garden, which was designed by Lakewood resident Theodore Wirth, is the second oldest public rose garden in the country.

The Rose Garden in 1955. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Ten years prior, in 1936, the Park Board designated another section of this donated land as a bird sanctuary. Now known as Roberts Bird Sanctuary (after famous ornithologist and Lakewood resident Thomas Sadler Roberts), the sanctuary is home to many species of birds, making for great birdwatching on Lakewood’s grounds, as well.

Lakewood and the Park System: Design is all in the (Cleveland) Family

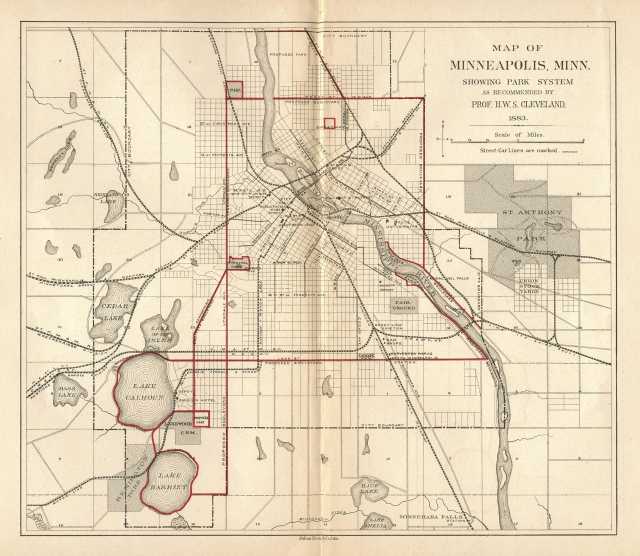

Not only was Lakewood linked to the park system by passionate leaders and advocates of public green spaces—they were also linked by the Cleveland family. Horace W. S. Cleveland is one of the most famous landscape architects in the history of the United States. Perhaps his most significant accomplishment was serving as the primary architect behind the Minneapolis Park’s city-wide “Grand Rounds” greenspace system.

Horace W. S. Cleveland’s 1883 map of the proposed Minneapolis Park System. Source: MNopedia

When Lakewood was first being designed in 1871, the Board of Trustees recruited notable cemetery designer C. W. Folsom. Folsom presented a strong case: he was the superintendent of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts, America’s first garden-style cemetery and a space that served as significant inspiration to Lakewood’s founders. But in 1884, Lakewood began to look very different. Ralph D. Cleveland, the son of Horace Cleveland, took over as the second Superintendent of the Lakewood Cemetery Association. It was under his guidance that Lakewood underwent a series of expansions, and ultimately grew to approximately the size and layout it is today.

Harry Wild Jones: The Architect of Public Space

In 1910, Lakewood Cemetery opened a building unlike any that had been seen in the United States. This building, the Lakewood Memorial Chapel, was designed by local architect Harry Wild Jones. Modeled after the Hagia Sofia Byzantine church in Istanbul, the Lakewood Chapel features an interior made up of over 10 million mosaic tiles. It was, at the time of its opening, the largest mosaic interior in the United States.

The Lakewood Memorial Chapel today

Architect Harry Wild Jones beat out national competition in the bid to design the Lakewood Chapel. And he was selected with good reason. By 1910, Jones had made quite a name for himself in Minneapolis. Born in 1859 in Schoolcraft, Michigan, he attended MIT and relocated to Minneapolis in 1884. Shortly after he arrived, he began working as a professor of architecture at the University of Minnesota. Around the same time, he began his 12-year tenure as a member of the Board of Park Commissioners. Between 1889 and 1932, Jones designed many public park and recreation buildings, including the Lake Harriet Pavilion (1891-1903), the Minneapolis Millers’ Nicollet Park (1896-1955), the Washburn Park Water Tower, and many more. He was known for expertly combining architectural elements from bygone eras with modern technology, with styles ranging from Medieval Revival, to Tudor, and classical Chinese-inspired designs. In his public park and recreation designs, he used architectural styles that were formerly reserved for the homes of the wealthy, making beautiful architecture more accessible to the masses. He also designed many churches and sacred spaces, making him a strong pick for the Lakewood Chapel architect. The Chapel has gone down as perhaps Jones’ most famous work, and is largely considered one of the finest examples of Byzantine Revival architecture in the United States.

The Washburn Water Tower as it stands today. Source: Wikimedia

Lakewood’s Legacy

Even as the Minneapolis park system grew, Lakewood remained a destination for those seeking comfort in nature. Minneapolis residents would regularly come to Lakewood just to stroll the grounds or to picnic. In the early 1900s it was a stopping point on the “Twin City Sightseer” trolley tour. Today Lakewood continues to serve as a public place of solace and natural beauty—a haven in the heart of the city.

Leaders like Charles Loring, George Brackett, and Thomas Lowry were enormously influential in making Minneapolis the beautiful, green, and park-centric city it is today. 12 years before the Park Board was founded, these leaders got their start at Lakewood Cemetery—arguably the city’s first large-scale public “park.” Other architects and influencers like Ralph D. Cleveland and Harry Wild Jones continued the connection between Lakewood and the city’s public parks. Unsurprisingly, each of these leaders opted to be memorialized at Lakewood. Horace Cleveland, Theodore Wirth, and even first park donor Edward Murphy are also laid to rest and commemorated forever at Lakewood.