This year marks the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War. At Lakewood, we’re paying special tribute to this anniversary at our annual Memorial Day Celebration by remembering those who served at home and abroad during the Great War. Part of our tribute will be a special history exhibit that explores what life was like for Minnesotans in 1918 through the stories of individuals now buried at Lakewood.

One of those featured will be singer and music professor Harry Anderson, Sr. Born in the 1880s in England, Anderson was immersed in the WWI-era Minneapolis musical community as a professor and choral leader. But his story is about more than music. It’s a story of community, patriotism, and the impact of WWI on Minneapolis’s musical and artistic legacy.

Harry Anderson, right, leads a community singalong in Powderhorn Park. Source: Minnesota Community Sings

Let’s set the stage. The United States was a tense place during WWI. Federal and local governments were suspicious of German-Americans’ ties to the Central Powers, who were vying for political, military, and imperial control over Europe. German-Americans were the largest ethnic group in Minnesota during the War. Many Minnesotans of all backgrounds were eager to display their loyalty to the U.S. and support the war effort.

There were a lot of ways for those on the home front to support the Great War. Women sewed bandages for injured soldiers. Children planted vegetables and grains in “Victory Gardens” so that large-scale food production could be directed toward the war effort. With suspicion rife, many Minnesotans (especially the 84% of the population that was foreign-born) could also use these public acts of support to demonstrate their allegiance to the U.S. and the Allied Powers. Parades dominated public spaces, raising morale and allowing Minnesotans an opportunity to put their patriotism on display.

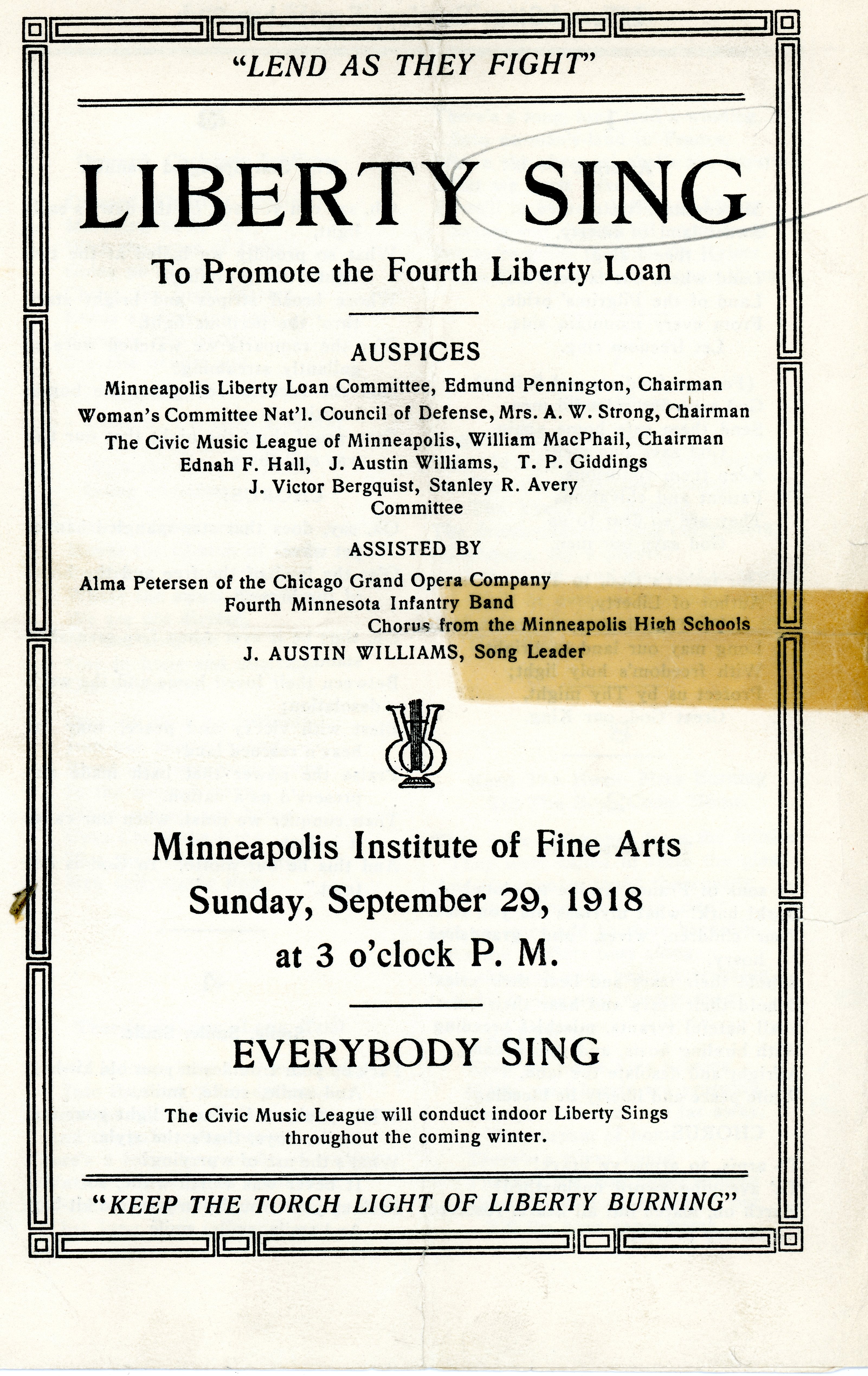

[endif]–One of the most interesting ways of raising morale on the home front was through music. Patriotic songs dominated popular culture during the War: 70% of popular songs copyrighted in 1918 were WWI songs. Starting around the time that the U.S. entered WWI in 1917, an organization called the Minneapolis Civic Music League (chaired by William MacPhail, who also resides at Lakewood) and the Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners hosted large-scale “sings” in many of the city’s parks—no audience, just participation. “Community Sings” of these patriotic and popular songs were led by neighborhood song leaders. These sings presented a way for residents to gather together to show their patriotism. It is even said that some local government officials would keep tabs on attendance in order to gauge individuals’ loyalty. Community Sings took place in every county and township in the state. It is estimated that 70,000 Minnesotans attended the group sings in 1918 alone.

A pamphlet from a 1918 community singalong. Source: Hennepin History Museum

Though Anderson wasn’t an official Community Sing leader until after the War, he was a linchpin of Minneapolis’s musical community during WWI. As a music professor at Augsburg College, he encouraged camaraderie between students and nonstudents alike by leading the school’s Glee Club to perform across the state. Small town newspapers of the nineteen-teens wrote glowing reviews of Anderson and his students.

Back in Minneapolis, Community Sings had been planned throughout the winter of 1918. But with the armistice of November 11, 1918, the original purpose of the sings was no longer as relevant. The practice could have disappeared altogether. But musicians like Harry Anderson and civic leaders like then Park Board Secretary J. A. Ridgway saw value in continuing to host these joyous neighborhood gatherings.

Thanks largely to Anderson, the practice of community singing didn’t only continue after the armistice—it grew exponentially, and gained Minneapolis national recognition as a musical city. Anderson served as the official Community Sing Director with the Minneapolis Park Board from 1920 until 1945, one year before his death. For many summers, Community Sings took place 6 nights a week in Minneapolis parks. Under Anderson’s guidance, Powderhorn Park set the record for the state’s largest Community Sing, where 15,000 voices rose together one summer evening in 1922.

Anderson was a master of drumming up public enthusiasm, and wasn’t afraid to introduce a bit of friendly competition. He issued challenges for the different hosting parks to compete in the areas of “attendance,” “enthusiasm,” and “deportment.” (Note that musical talent was not in the equation!) After the evening’s celebrations, Anderson would take the streetcar down to the headquarters of three different local papers, where he would prepare published summaries of the gatherings and report on the various parks’ standings. All the while, Anderson continued instructing at local colleges, led several church choirs, and taught private vocal lessons out of his downtown studio.

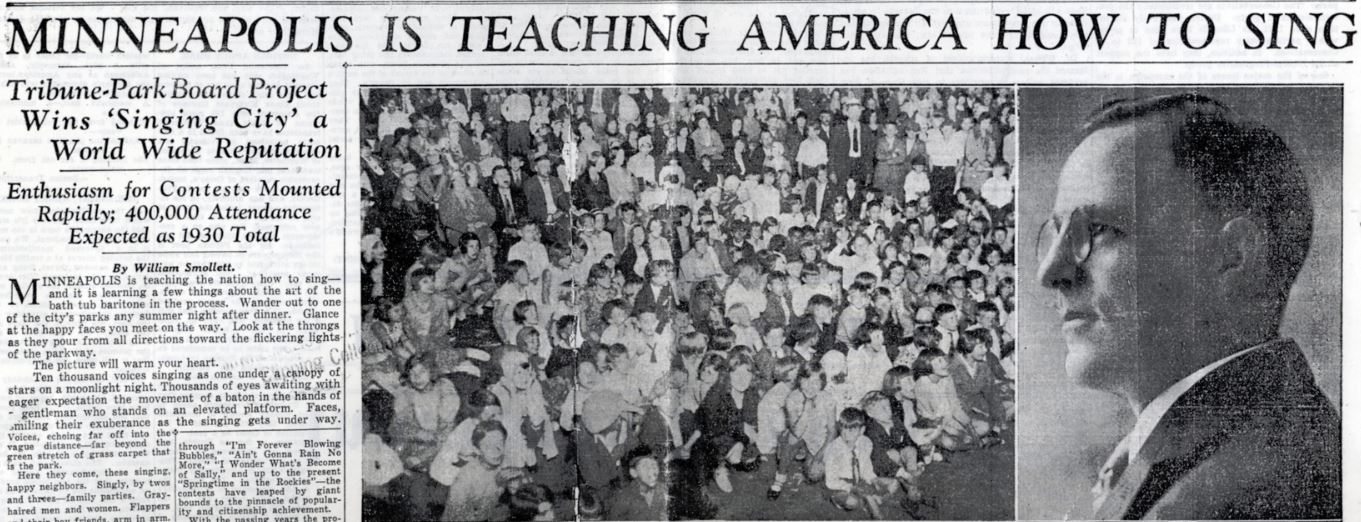

The participatory, community-driven entertainment of Community Sings was very popular until the 1950s, with Anderson at the helm for much of the time. In 1930, a newspaper headline announced, “Minneapolis is Teaching America How to Sing.” This article lauded Anderson for his efforts, and dubbed Minneapolis “The Singing City.” In prosperous times, community singers were often accompanied by a 15-piece band. In the austerity of the Great Depression and WWII, thousands of neighbors would sing with the support of just one piano. But regardless of the era, attendance—and spirits—were enormously high.

A 1930 article from the Minneapolis Tribune. Harry Anderson is featured on the right.

Anderson was devoted to patriotic causes until the end of his life. He served as the Park Board’s Community Sing Director throughout WWII, all while chairing the local draft board. Harry Anderson died of cancer in 1946, the year after the Second World War ended. He was buried near the former streetcar entrance on Lakewood’s west side.

During World War I, music was a way to raise spirits and demonstrate patriotism. But the even greater takeaway for the people of Minneapolis was the joy of being in harmony with your neighbors. Thanks in part to Harry Anderson, Minneapolis became a city known for its music. This legacy continues today.

Special thanks to Minnesota Community Sings for research assistance for this blog post!

![endif]–