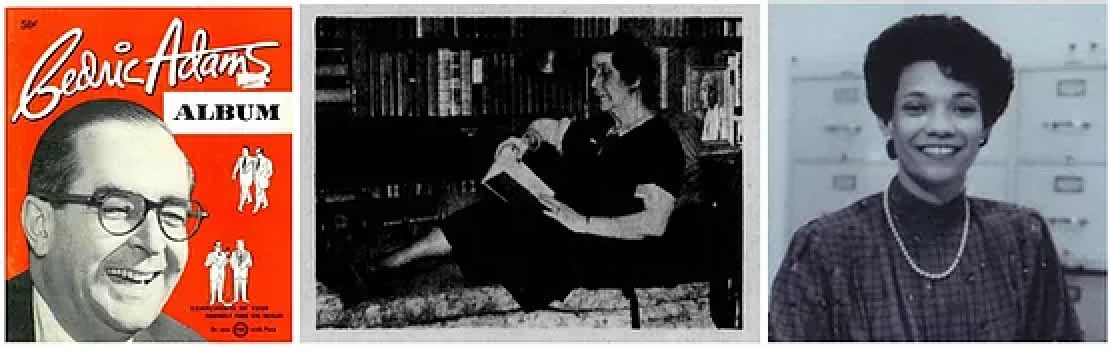

Now more than ever, we rely on media outlets to keep up to date with the issues that impact us all. All month on our Facebook page, we have been honoring the journalists, editors, engineers, radio-tinkerers, and media advocates who have helped create a diverse, informative, and entertaining media network in the Twin Cities over the last 150+ years.

Before there was radio, television, or the internet, newspapers were the way to keep in touch with the latest happenings, from down the block or around the world. Minnesota’s first newspaper, the Minnesota Pioneer, started in St. Paul in 1849, shortly after colonizers established Minnesota as a territory. Two years later, there were five consistently-published newspapers in the territory—a high number considering Minnesota had just over 5,000 residents. Minnesota defined itself early as a media and information hub.

The first newspaper in what we now call Minneapolis was started in 1851. (It was established in what was then called St. Anthony, now Northeast Minneapolis.) More newspapers followed. But running a newspaper in the early days of the Twin Cities was no small task. Newspaper owners often also served as reporters and editors. The work was known to be exhausting, and newspapers in these early years were often short-lived.

It wasn’t until May of 1867 that Minneapolis got a daily (or 6 day a week) newspaper with staying power. The Minneapolis Daily Tribune released its first issue on a Saturday morning. In that first issue, readers of the newspaper learned of a fire in New York, a battle in Mexico City, and the current prices of grain and cattle at Minneapolis markets.

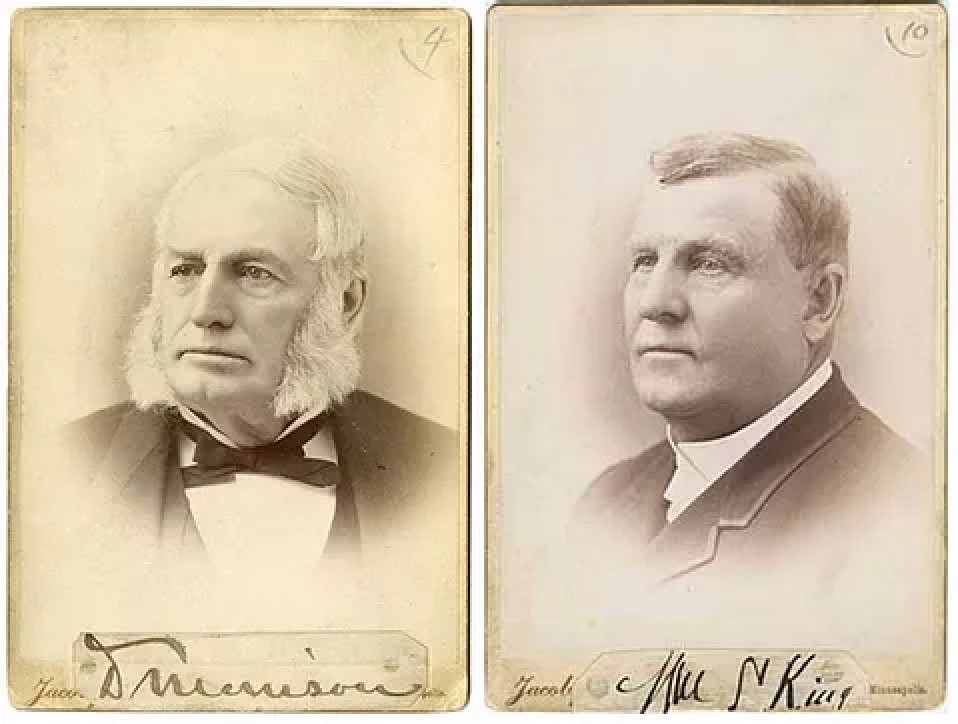

In addition to the details of disasters and market news, readers of 1800s newspapers could also find a number of opinion pieces. In the 1800s, journalism wasn’t expected to be impartial. It wasn’t until the 1920s that objectivity became a professional ideal of journalism. Most newspapers were tied to specific political parties, municipalities, or labor organizations. The Tribune, for example, was owned by politicians and businesspeople, including Minneapolis’s first mayor Dorilus Morrison. Another Tribune founder, businessman William King, eventually served in the Minnesota House of Representatives. Prior to the Tribune, Morrison and King had dabbled in the newspaper business in what was then the small frontier town of Minneapolis. But in 1867, just a few months after the City of Minneapolis was officially incorporated, the two closed up their other papers and focused on the Tribune, which operated out of downtown. Morrison and King are both buried in Lakewood’s Section 2, the cemetery’s oldest section.

With an experienced staff, a social and political message that resonated with many in Minneapolis, and the backing of investors, the Tribune grew. The Tribune eventually became the Star Tribune, which still operates today.

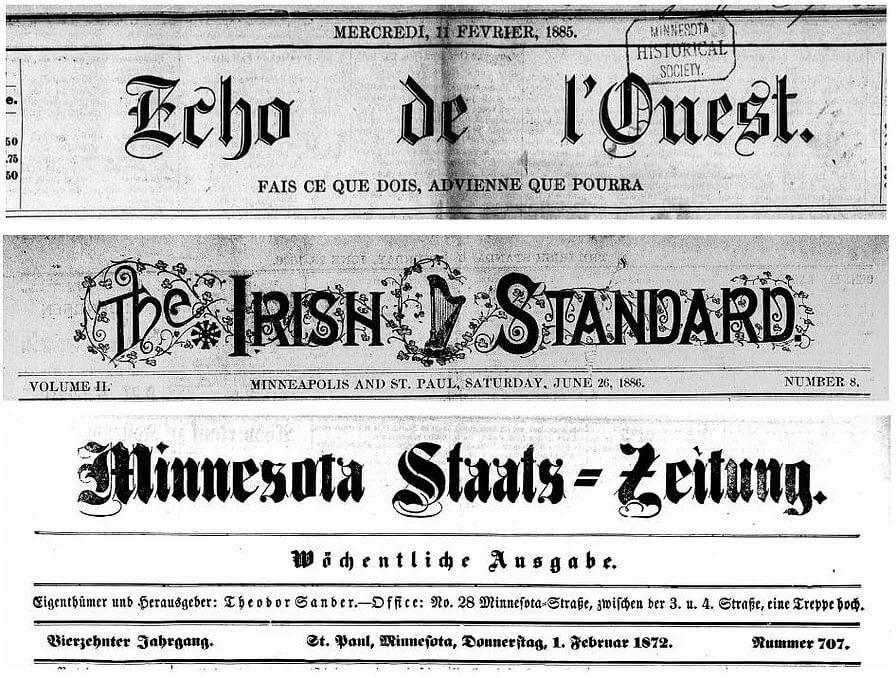

Large newspapers like the Tribune kept readers informed of the news across the country and around the world. But other early newspapers in Minnesota served another crucially important purpose: they were a lifeline for cultural communities. In 1867, the Minnesota legislature created the State Board of Immigration to promote immigration to MN. They placed ads in foreign newspapers, promoting immigration to the Twin Cities.

These ads worked. And as immigrant communities grew in the Twin Cities, many culturally-specific and language-specific newspapers were born. One of Minneapolis’s early Swedish newspapers was Minnesota Stats Tidning. The paper, which was created in 1877 and ran until 1939, was co-founded by early Swedish immigrant Hans Mattson. In addition to helping create this early Swedish American paper, Mattson was also a Colonel in the Union Army and served as Secretary of State. Mattson is buried in Lakewood’s Section 10. In the 1890s, a popular Norwegian newspaper called the Minneapolis Tidende was founded. One of it’s most influential editors, Carl Gustav Otto Hansen, is buried in Lakewood’s Section 36.

The importance of mother tongue newspapers is made clear by the inscription on the grave of Swedish immigrant Dr. Charles Borglund, who died in 1911. The inscription reads:

In remembrance of Dr. Charles Borglund, editor of the Forskaren, 1898-1911. The world was his country, to do good his religion. The readers of the Forskaren erected this memorial in the year 1917.

Borglund (1869-1911) was an immigrant to Minnesota and the creative engine behind the progressive Swedish-language newspaper/magazine the Forskaren, or “Investigator,” which ran from 1894 until 1924. The paper/magazine, which Borglund ran out of his office at 1119 Washington Avenue South, was read from Massachusetts to Oregon, and up to British Columbia. It was especially popular in small-town Minnesota. Borglund himself contributed columns on politics, covered news in Sweden, and published many thinkpieces. Borglund’s presence must have been greatly missed among his local Swedish readership, who erected Borglund’s beautiful headstone at Lakewood more than five years after Borglund’s death. Borglund is buried in Lakewood’s Section 21.

In addition to Swedish papers, Twin Cities residents created French, German, Danish, and Irish newspapers. There were papers published by leaders of the labor party. The American Jewish World was established in the 1910s, and still operates today.

The early Twin Cities also had a thriving Black press. The Western Appeal (which became the Appeal) started in 1885, and reported widely on local and national news. They placed an emphasis on news relevant to the Black community, much of which was not being published in white newspapers. In addition to reporting and publishing, members of the burgeoning Twin Cities Black community were also seeking to reverse a severe drought of Black professionals in the Twin Cities; they ran ads in Black-owned newspapers across the country to promote the residential and employment potential of the Twin Cities. Their efforts, too, were successful, and the Black community grew larger. To serve the cultural and community needs of the growing population, more Black-owned newspapers were published around the Twin Cities.

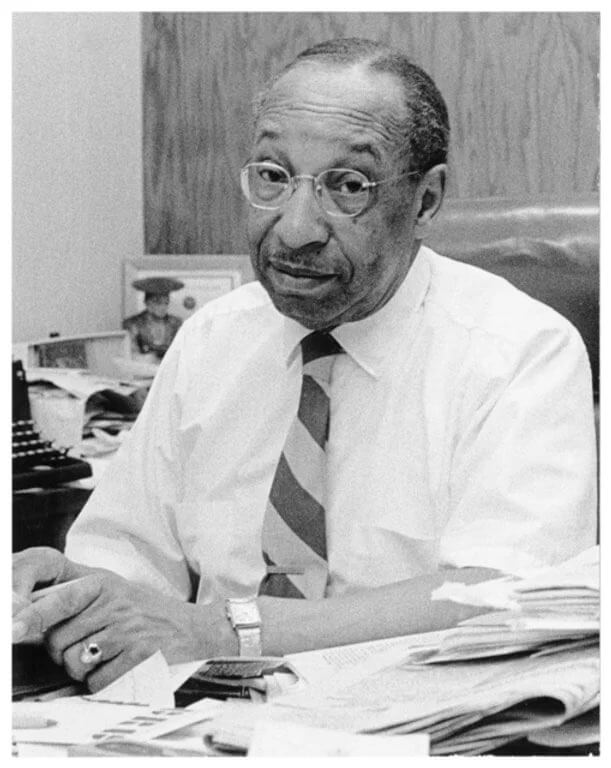

One of Minnesota’s most influential Black newspapers was the Spokesman Recorder (now the Minnesota Spokesman Recorder), founded by Cecil Newman. Born in 1903 in Kansas City, Newman developed a passion for journalism as a child, delivering papers and working in the back office of a Black-owned newspaper. He moved to Minneapolis in 1922, shortly after graduating high school. Here he contributed to the local Black press while working as a railway porter. Amidst the Depression, Newman was able to quit his porter job and focus entirely on journalism. In 1934 he founded two successful Black newspapers: the Minneapolis Spokesman and the St. Paul Recorder. The papers eventually merged and became the Minnesota Spokesman Recorder. Newman’s paper’s editorials were used to keep politicians accountable, advance the causes of integration, and promote demonstration against discrimination at local businesses. Newman went on to become the first Black president of the Minnesota Press Club, and worked actively until his death in 1976. Newman is interred in Lakewood’s Memorial Mausoleum. The Minnesota Spokesman Recorder still operates today.

Newspapers were a crucial source of information and an essential connection to community for many early Minneapolitans. Today, the Twin Cities continues to live up to the legacy of robust media coverage established by these early newspaper founders. The Twin Cities remains a hub for deep and diverse journalism, news, and entertainment. Minneapolis is still home to many English language and non-English language newspapers, as well as radio programs, television shows, podcasts, and more. We are grateful for media trailblazers—from Dorilus Morrison, to Hans Mattson, and Cecil Newman—and for all those they inspired.