It’s August, and we’re getting ready for the Great Minnesota Get-Together! This month, we’re looking at the Minnesotans who helped shape our state’s entertainment and amusement culture. Perhaps the most intriguing of all early Minneapolis entertainment entrepreneurs was Lakewood resident Robert “Fish” Jones. Jones had a major influence of the Minnesota State Fair by helping to bring legendary racehorse Dan Patch into the limelight. But he also built a minor empire of amusements in Minneapolis.

It’s 1876. You’ve just moved to the burgeoning city of Minneapolis from the East Coast. The small but growing city is now home to over 20,000 people and boasts a horse-drawn trolley system, but it seems small for your East Coast sensibilities. As you visit local establishments and ask for a meal of seafood to satisfy your coastal cravings, you’re repeatedly told that such a meal isn’t sold in Minneapolis. A lightbulb goes off. If you’re entrepreneur and showman Robert “Fish” Jones, you reach out to your friends out east, utilize that new refrigerated railcar technology, and open a fish market at 308 Hennepin Avenue. The city’s growing urban population is eager for some East Coast class, and your market takes off immediately.

No Ordinary Market

Despite nearly instantaneous success, Robert “Fish” Jones wasn’t satisfied. He wanted to further set his shop apart. So, like the eccentric businessman he was, Jones purchased a bear. The two made quite a pair as they sat on downtown’s Hennepin Avenue greeting passersby. Jones was always dressed in a fine suit, silk top hat and high heeled boots. Unsurprisingly, the bear was a hit. So Jones expanded his animal collection. He housed his new animals on the 3rd floor of his downtown warehouse and shop space. Here he showcased rare birds, fish and turtles, and even seals. Robert “Fish” Jones became a well-known, if eccentric, figure around Minneapolis. Rumor has it that Jones even took President Ulysses S. Grant on a carriage ride up Nicollet Avenue during Grant’s post-Civil War world travels.

Lions and Horses and Bikes – Oh My!

In 1885, after running the fish market for 7 years, Jones decided to enter fully into the business of animals and entertainment. He purchased a home on what was then the outskirts of town (16th & Hennepin). Here he raised and displayed lions, tigers, monkeys, camels and Russian wolfhounds.

Meanwhile, Jones maintained his business ventures by opening the Minnehaha Track. Founded in 1888 and located between 36th & 37th Streets on South Minneapolis’ Snelling Avenue, Minnehaha Track was a one-stop shop for local amusements. At this time, horse, bicycle, and auto racing were big in Minneapolis and across the country. The public was mildly obsessed with testing the limits of the human (and animal) body, and the potential of new technologies like the car. With varying degrees of success, Jones tried his hand promoting each type of race. Minnehaha Track, though always under construction and in flux from surprisingly consistent under-performance, hosted many auto races, bicycle races and horse derbies.

Within the track you could find a baseball diamond, where the Minneapolis Millers and smaller local baseball teams would compete (including on Sundays, though Sunday baseball was banned in the city). Jones even welcomed a “diving horse” show, where horses would jump off of a 40 foot platform into a pool below. Minnehaha Track was a haven of thrills.

A local newspaper promotes a 1902 horse show and race at Minnehaha Track.

Source: St. Paul Daily Globe via Chronicling America

Clearly, times were different in the late 1800s. The Minneapolis Humane Society didn’t exist until 1891, and the federal Animal Welfare Act wasn’t signed until 1966. But shortly after the Humane Society was formed, they (reasonably) mandated that Jones make some changes — particularly around his home on Hennepin Avenue. The neighbors complained when Jones’ lions would roar in the middle of the night. Jones also received some flack for his treatment of animals after parading a camel down a major Minneapolis street on a snowy winter day; he responded to this complaint by commissioning a knit pants and a sweater for the camel. But Jones’ days at 16th & Hennepin, and even at Minnehaha Track, were numbered. Lucky for Jones, his eccentric promotions paid off, and other opportunities knocked.

Longfellow Zoological Gardens

In the early 1900s, the Twin Cities’ Rapid Transit streetcar company wanted to attract more riders by opening a zoo at the end of their trolley line near Minnehaha Falls. Jones was the obvious choice to acquire the animals. At the direction of the company, Jones purchased a whole entourage of new animals. But shortly thereafter, the trolley company backed out of the plan altogether.

Jones, ever the creative entrepreneur, made the most of this setback. He purchased land near the falls and opened his own zoo with his updated fleet. At the same time, the Minneapolis Park Board gifted Jones a variety of donated animals that they had kept in an informal zoo. The only stipulation was that Jones’ zoo must be open free of charge one day each week.

Jones’ Longfellow Gardens was an enormously popular summertime attraction.

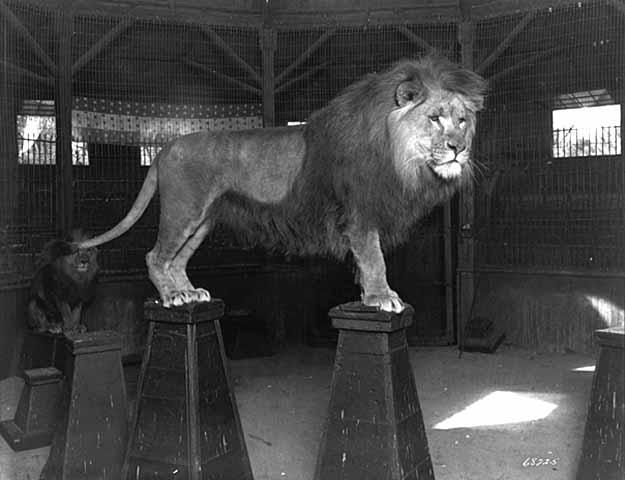

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Jones opened the “Longfellow Zoological Gardens” in 1907. And it was a huge hit. Tens of thousands of visitors streamed through the gates to soak up the summer sun and see Jones’ ever-evolving collection of animals. Jones, always in his suit and top hat, fed seals on the grass — without cages — as crowds of children and adults gathered to watch. Swans and pelicans wandered the grounds. Guests could stroll the grounds and walk into the pavilion for a circus-style lion taming show, or catch an exhibition of Jones’ prized wolfhounds. Visitors rode camels around the park’s paved paths, and Jones tantalized crowds as he fed bears much bigger than him while separated only by a few steel bars.

Jones plays with bear cubs at Longfellow Gardens, 1925.

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Lions take the stage at Longfellow Gardens, 1927.Source: Minnesota Historical Society

But don’t think that Jones was simply an eccentric showman. No, he was also a seasoned reader and lover of poetry. His favorite poet was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, whose published the famous “Song of Hiawatha” poem in 1855. The poem was based on fabricated accounts of the Native population in the area that became Minneapolis, and propelled the myth that Native people voluntarily “left” to make way for the settler population. Nonetheless (or perhaps for this very reason), Longfellow was celebrated by many early Minneapolis settlers. When Jones moved to the area surrounding the Minnehaha falls in 1906, he built himself a ⅔ scale replica of Longfellow’s Massachusetts home. He lived here until his death. In 1908, he dedicated a statue of Longfellow on the site of the gardens. The home and the statue remain at the site today.

The Longfellow House today.

Source: Minnesota School of Botanical Art

Jones, however eccentric, was not strictly outside the mainstream. His park attracted a variety of guests, and was indeed one of the biggest destinations for visitors to the Twin Cities. Jones even collaborated with local prohibition advocates; in 1916, he lent a camel to the National Prohibition Parade, which was held in St. Paul. This camel, which the parade organizers aptly named “Ann T. Booze,” led the parade.

But not everyone loved Jones’ endeavors. In 1922, the Park Board expressed interested in using the Longfellows Gardens space for a new playground (which was never built). Two years later, a group of neighbors banded together and petitioned the city to shut down Jones’ zoo. Jones eventually agreed to donate the land to the Park Board, with the stipulation that he could operate the zoo for ten more years. Jones passed away in 1930, before these ten years were up. After Jones’ death the Park Board took control of the property. In 1934, his children oversaw the distribution of Jones’ animals to other local zoos, including Como Zoo. Seven years after Jones’ death, his home (the Longfellow replica) was made into a public library branch.

Today, the Longfellow Gardens are a local favorite for walks among diverse flora. Jones’ home serves as an information center for the falls and the Ground Rounds system, and houses art classes and events. The keen observer can take a stroll off the beaten path and see the Longfellow statue among Minnehaha Creek’s sloping banks and tall grasses.

The Longfellow statue today is no longer at the center of a busy zoo.

Source: Minneapolis Parks & Recreation Board

Robert “Fish” Jones was one of early Minneapolis’ most eccentric and memorable characters. But despite his uniqueness, Jones’ amusement empire exemplified a common trend in early American cities. In these growing industrial hubs, there was an ever-increasing population of residents ready to pay for entertainment. While State and County Fairs celebrated local feats in agriculture and industry, urban sites like zoos and race tracks became thrilling spaces where proprietors tested the limits of human and animal bodies, as well as the limits of new technology like bicycles and automobiles. And the public ate it up.

Jones was a city boy through and through. But working in the animal/livestock industry meant that he was also inextricably linked to the more traditional agricultural fairs, like the Minnesota State Fair. Stay tuned for Part 2 of this blog post, where we explore Jones’ connection to the Minnesota State Fair and the famous racehorse Dan Patch.

Read Part 2 of Robert “Fish” Jones Entertainment Empire, where we explore “Fish” Jones’ connection to legendary Minnesota State Fair racehorse Dan Patch, and how Patch altered the State Fair forever.