What comes to mind when you think of an epitaph? A favorite quotation? A mournful poem? A simple series of dates and a phrase like “rest in peace?”

An epitaph is a phrase or words written in memory of a person who has died, especially as an inscription on a marker or monument. They serve a variety of purposes. They can tell us a bit about the deceased, such as their military service or proclaimed faith. Some read like resumes, listing accomplishments, or include humorous lines that give us a sense of the deceased’s personality. Many provide a record of migration, with early settlers or migrants often listing their birthplace on their gravestone.

The grave of Clyde Earl Hagen lets us in on Hagen’s humorous side.

The nearby grave of Henry Hagen tells a story of migration.

But epitaphs didn’t always serve such personal or emotional purposes. And the ways our final messages have changed over time mirror broader cultural changes in our relationship to death.

When graves bore names, dates and skullsIn the 1600s and into the 1700s, death was a tangible part of everyday life. Life expectancy in the US was usually in the 30s, and infant mortality was high. Dying was not a medical event — instead it took place in the home, with people of all ages interacting directly with the realities of death.

During this time, epitaphs and grave imagery echoed this practical viewpoint. Epitaphs often included the name of the deceased, a birth date, and a death date. “Here lies the body of…” they read, using very earthly language. The imagery of the graves also reflected the physical reality of death. The skull — a common image on European gravestones, imported by settlers to the colonies — was not intended to be grim, but rather a matter-of-fact reminder of the inevitability of death.

A 1743 grave in New York City’s Trinity Church Yard, featuring a winged skull. Source: Urban Omnibus

After the funeral industry emergedLater in the 1700s, epitaphs began to change. From the blunt language of death and images of skulls, we begin to see more euphemistic language for death, such as “resting,” “asleep,” or “at peace.” This change was not a coincidence. In 1759, the US’s first funeral home opened. During the industrial revolution, the “funeral industry” began to take off. For the first time, professionals in the US were paid to handle the body of the deceased and “undertake” the funeral and memorial process. Many people interacted with the dead significantly less than they may have 100 years prior. Life expectancy eventually grew longer. And over time, death became something that took place in hospitals, rather than at home. For many Americans, death was becoming less tangible.

As fewer and fewer Americans were interacting with death on a daily basis, the language of epitaphs became more ambiguous and gentle — it became more common for American graves to bare images suggesting rebirth or an afterlife, such as flowers, birds and religious emblems.

In Minnesota, it’s uncommon to find a grave with a “death’s head” image in a cemetery like Lakewood, which was founded in 1871. Shorter epitaphs usually just list a name, birth year and death year, rather than using the more explicit language of “died,” or “here lies the body.”

Around the same time, we see another shift in the content of epitaphs. It is a shift in the focus of the text — from the person who died to the people left behind. Some monuments in the 1800s and early 1900s include text about who erected the monument, and how much the deceased is missed by the survivors. Epitaphs started providing information not just about the dead, but about the living.

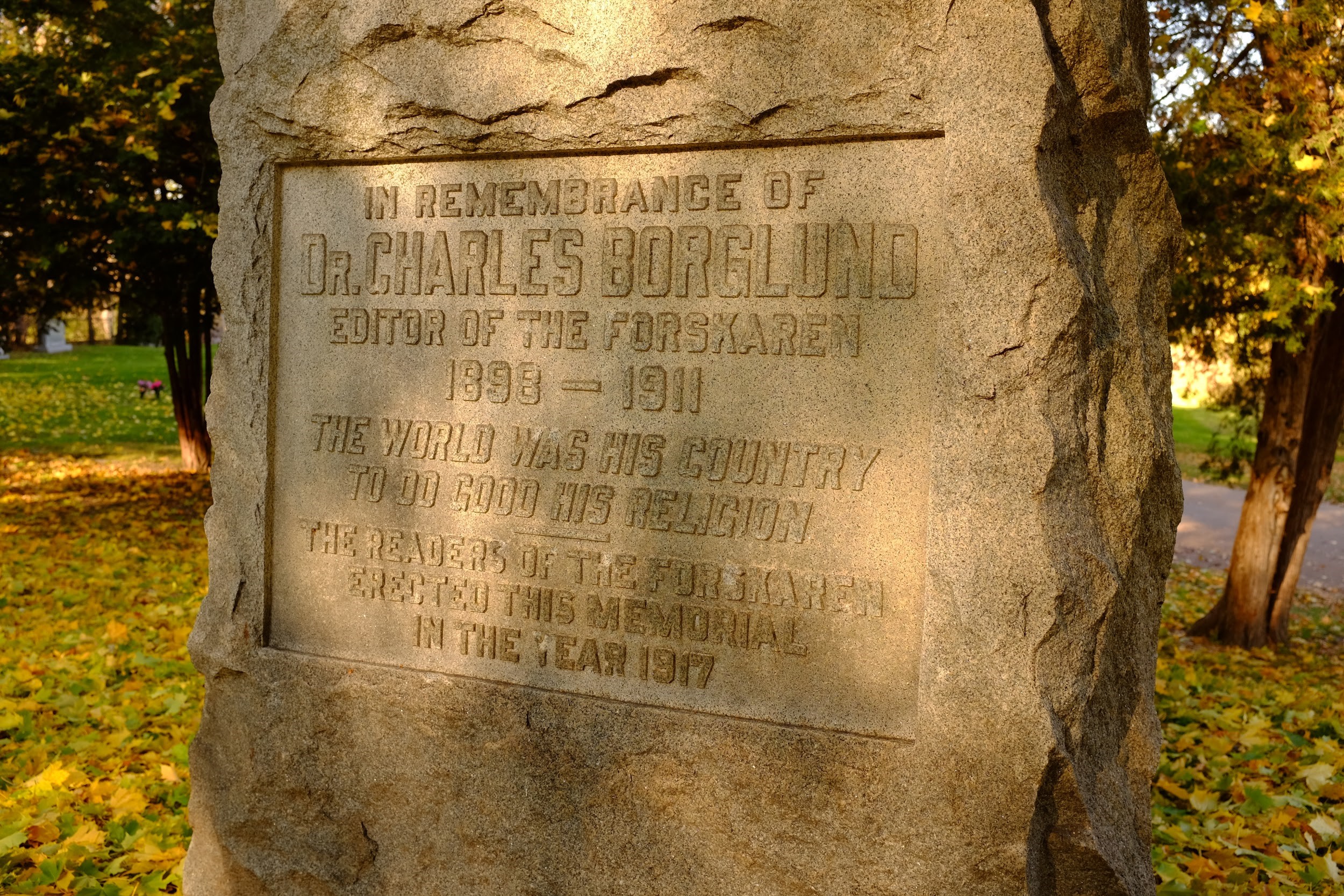

These three gravestones at Lakewood include information about the people who erected the monument, not just the deceased.

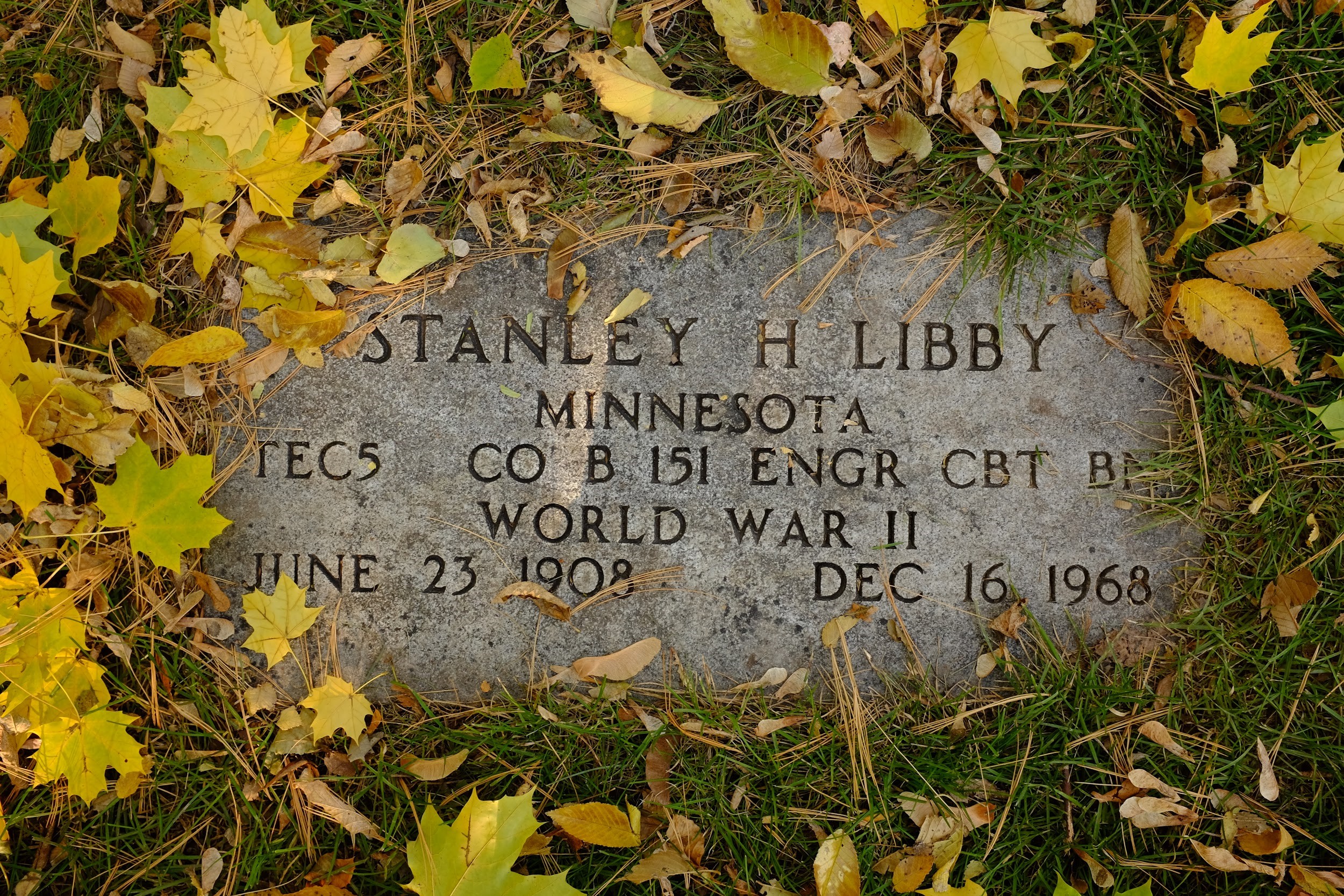

Also in the late 1800s, it was becoming more common to include military service and accomplishments on gravestones.

Many gravestones at Lakewood tell of military service.

“Remember Me”

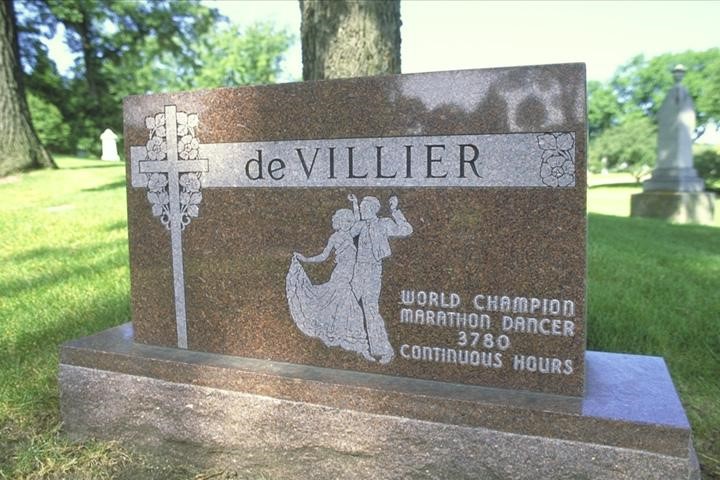

The idea that people use their epitaphs to say “remember me” to passersby is relatively new. A few people, like Sir Joseph Francis, whose grave site overlooks Bde Maka Ska (formerly Lake Calhoun) from Lakewood’s Section 1, used epitaphs to list their accomplishments (including inventing a safer lifeboat and being honored by Congress) as early as the late 1800s. But this approach became more popular in the mid-1900s, as is evidenced by the graves of Richard G. Drew (d. 1980), whose grave marker reads simply, “Inventor of Scotch Tape,” or Callum deVillier (d. 1973), whose marker reads “World Record Marathon Dancer.” These graves beg passersby to learn more.

The graves of Richard G. Drew and Callum deVillier, both of whom’s epitaphs name a major accomplishment.

Today people find meaning at a time of loss not just through memorial markers and epitaphs, but through celebrations of life and meaningful time spent at places devoted to remembrance.

Some people have returned to the simple approach of listing a name, birth dates and death dates. Others express their passions using engraved images like classic cars, picturesque scenery and musical instruments. Just like epitaphs of bygone eras, so too will our present-day monuments pique curiosity of passersby for generations to come.