In 1850, a man in his late 20s named John Orth arrived in the frontier town of St. Anthony. Born from a contested territory between Germany and France, Orth noticed a conspicuous vacancy in this burgeoning settler outpost that we now known as Northeast Minneapolis. What was missing from this town, Orth thought, was beer.

It wasn’t that the settlers in St. Anthony hadn’t had beer before; people across class lines brewed the popular, intoxicating beverage in their homes. But homemade ales weren’t often lauded for their flavor, and they were usually loaded with sediments left over from the brewing process.

Orth, however, knew some secrets of the trade; he had been brewing since he was young. And he also knew about a new type of beer that was changing the game in the mid-1800s: lager was lighter and tastier.

A label for John Orth’s lager beer. Note that the label says the beer is “for family use.” That is because many early American beer companies tried to market their product as a health tonic, claiming it was safe, and even healthy for children in small amounts. Source: City of Minneapolis

But lager wasn’t so easy to make. It had to ferment for a long while, and be kept at a consistent, cool temperature. Before refrigeration was widely accessible, this was hard to achieve.

John Orth took a risk. He dug caves into the bedrock of Nicollet Island, where the year-round temperature of about 55° made it possible for him to brew his lager year-round. In a tiny wooden shack, smaller than two city buses sitting side-by-side, he opened the city’s first commercial brewery. The risk paid off. Early settlers on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River liked his product.

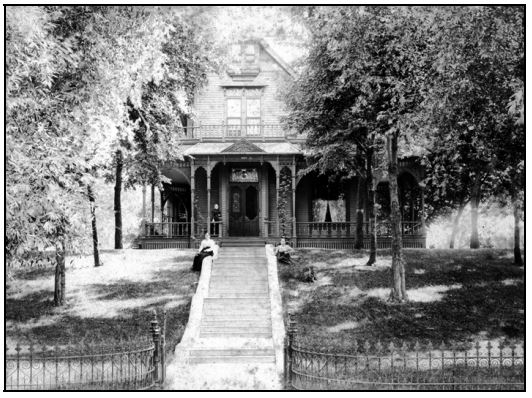

By 1875, Orth Brewing Company was the region’s biggest brewery. John Orth moved out of his small home in Northeast, and into a mansion nearby. Late in their lives, he and his wife traveled to Europe and Africa while their sons took over the business.

John Orth’s grand home (now demolished) was a show of his business success. Source: City of Minneapolis

Meanwhile, other breweries were bubbling up in Minneapolis. Most were started by German immigrant families who were seen as experts for having learned brewing in their homeland, or from family recipes. In addition to the Orths, Lakewood residents the Glueks and the Heinrichs were operating successful breweries in Minneapolis by the 1880s. The popularity of the product grew — so much so that by 1908 there were 432 official saloons in Minneapolis alone.

A Gluek saloon in downtown Minneapolis, 1919 (one year before Prohibition). Source: Minnesota Historical Society

The Temperance Movement: Rooted in Responsibility

Some Minnesotans drank responsibly. The saloons became social hubs. They were places to decompress after work, make friends, and even hire workers. But others found it unable to drink in moderation.

In the 1800s and early 1900s, the ills of alcohol got the best of many Americans. In the years before the 1850s, the average American man drank the equivalent of more than 60 one-liter bottles of hard alcohol a year — and that accounts for the many Americans who did not drink at all. Since the early days of Minnesota’s statehood, people from the city to the country advocated loudly for moderation, or even total abolishment, of alcohol.

Prohibition proved ineffective in hindsight, but the leaders of the temperance movement had good reason to be concerned. There were abundant accounts of public drunkenness and missed work. Some men stayed out at the saloons all night after work, or returned home intoxicated and violent. Many Minnesotan families starved as their primary breadwinners squandered their paychecks at the saloons. Some saloons even cashed laborers’ paychecks right there at the bar. The scene was especially bad in the early-1900s in Minneapolis, when politicians were known to secretly allow saloons to run as dens of vice, turning a blind eye to gambling and coercive prostitution.

The temperance movement found a strong foothold in the Midwest. Many Minnesota counties went “dry” (alcohol-free) before Prohibition started in 1920. This made brewers nervous — so nervous that some brewers like John Orth, who was involved in Minneapolis city politics and had previously identified as a Republican, switched to the Democratic party as Republicans grew more supportive of Prohibition. Political propaganda was abundant, with Republicans asking Minnesotans when enough was enough, and Democrats posting signs asking residents if they really wanted to be completely alcohol-free.

Minnesota women picketing in support of prohibition in 1917. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

The temperance movement gained even more momentum during World War I. Local and national leaders of the anti-alcohol group the Women’s Christian Temperance Union carefully crafted their message to paint alcohol as unpatriotic.

Here in Minnesota, the WCTU was run by Lakewood resident Rozette Hendrix as World War I ramped up. Rozette’s union played to the national interest in conserving food and resources for the war effort. They made propaganda posters touting the importance of sending domestic grains to troops abroad, rather than using it to make beer. Hendrix and her fellow campaigners were successful: many counties in Minnesota went “dry” (without alcohol) during WWI, and Minnesota passed statewide Prohibition before the federal law was passed.

How Minnesota Breweries Survived Prohibition — Or Didn’t

Minnesota breweries had to dump out all of their existing beer when Prohibition went into effect. Source: Stearns History Museum via Pinterest

In January of 1920, the hammer came down. Prohibition was going into effect. The last of the beer was sold (legally, at least), and breweries across the country were shuttered. Some Minnesotans, like Lakewood resident Ellsworth Norton Young, saw a world of opportunity in Prohibition. Already nearing 60, the downtown Minneapolis tailor changed career paths and started making sweet, flavored syrups for soda fountains and home use. His company “Brazilla” included yerba mate in their products, which was supposed to bring a light buzz to those who were looking for a legal pick-me-up. Glueks and the Minneapolis Brewing Company (which was created when the Orth and Heinrich breweries merged with two other local breweries) survived for many years by producing soda and “near-beer” (0.5% alcohol). Other breweries were known to use their existing cold storage rooms for the production of ice cream. Just barely, some large breweries managed to stay afloat during the dry years.

A 1920 ad in the Bemidji Daily Pioneer reveals that Brazilla’s “mystery ‘cheerfulness’ ingredient” was yerba mate. Source: Chronicling America

Many smaller breweries weren’t so lucky. They closed their operations. But others were ready for action when Prohibition officially ended on December 5, 1933. At the stroke of midnight, the Minneapolis Brewing Company and Glueks jumped immediately back into production.

An Enduring Legacy

The end of Prohibition brought with it a new series of strict laws regulating alcohol. But through periods of growth, loss, consolidation, and ownership changes, many long standing Minnesota breweries have maintained a connection to the state. Orth and Heinrich’s flagship beer, Grain Belt, is still produced in Minnesota by Schell’s in New Ulm. And in 2017, after more than 50 years without production, Glueks returned to the shelves; today it’s made just a mile away from the location of the first Gluek brewery in Minneapolis.

The story of beer in Minnesota is a story of immigration, family business, politics, and passion. And a visit to Lakewood shows that the connections made in life did not end at death: The Orth family plot is located right next to the Heinrich family memorial. And nearby, you can find the grand, eternal resting place of the Glueks.

Celebrate Oktoberfest with a visit to the graves of these pioneering Minneapolis brewers. You’re always welcome to visit Lakewood when our gates are open.