In these uncertain times, many of us are reflecting on the things we are grateful for, and what we cherish about our local community. One of the things that has long made Minneapolis a beautiful, vibrant city is its diversity—of thought, of experience, of people.

This month on our Facebook page we celebrated our city’s Book History by featuring the authors, librarians, and philanthropists who helped create a thriving literary scene in Minneapolis since its founding. In today’s blog post we share the stories of three great writers, now laid to rest at Lakewood, who used their literary talent to teach children—our future leaders—about diversity. These authors are W. Harry Davis, Borghild Dahl, and Mary Jackson Ellis. They knew that Minnesota’s children needed stories as diverse as our communities—both to teach them about people different from themselves, and to ensure them that they were not alone in their experiences.

From left to right: Borghild Dahl, W. Harry Davis, and Mary Jackson Ellis. Sources: The Norwegian American, Wikimedia, Jet Magazine

Civil rights leaders W. Harry Davis (1923-2006) was born in North Minneapolis to a Black American mother and a Winnebago Dakota father. He is best remembered for his 20 years of service as a member of the School Board, which began in 1969. After joining the School Board (where he was, for a period of time, the only African American member), Davis was the first board member to call for a comprehensive plan to desegregate the city’s schools. He advocated fiercely for integration—so much so that he had to keep his phone off the hook to avoid endless threatening telephone calls. His desegregation efforts were successful in 1971, when the all-white Hale School merged with the nearby Field School, which was overwhelmingly African American. The school was intended to be a model for integration.

In addition to serving on the School Board, Davis was also a firm and unifying community organizer, spending the 1960s and 70s working with politicians, police, and community organizations to fight poverty and segregation. In 1971, he became the first African American Minneapolitan to run for mayor with a major party backing.

Children at Minneapolis’ Sumner Field in 1936; W. Harry Davis second row, third from right. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

In addition to his antipoverty and desegregation work, Davis was also a keen athlete. Despite having childhood polio, he was a champion high school boxer. Davis had been a strong advocate for community sports since the early 1940s (right after he graduated high school), when he began his 18 year career as boxing coach at the North Side’s Phyllis Wheatley Community Center—a hub for many members of Minneapolis’ African American community at a time when they were excluded from many other city establishments. Davis stayed involved in boxing throughout his life, and even coached the 1984 Olympic boxing team, which took home nine gold medals.

In 2002, W. Harry Davis released an autobiography called “Overcoming.” This autobiography documented a lifetime of working to fight racism in all realms of Minneapolis life—from business, to politics, to sports. This autobiography, intended for adult readers, won a Minnesota Book Award.

But Harry Davis must’ve known that children, perhaps even more than adults, needed to hear this story, too. The next year, Davis released a history of Minnesota’s Civil Rights movement called “Changemaker” specifically for young readers. This book told the story of the movement through the lens of Davis’s personal memories and experiences, allowing children to understand that “history” doesn’t just live in textbooks—it impacted (and continues to impact) our neighbors, friends, families, and community members.

W. Harry Davis’ autobiography “Overcoming” won a Minnesota Book Award. Source: Amazon

W. Harry Davis remained active in community groups until late in life, and was repeatedly lauded for his decades of community service. He received at least 79 civic leadership awards in his lifetime, and is the namesake of a scholarship and a foundation. Davis died in 2006 at age 83, and is buried in Section 53 at Lakewood.

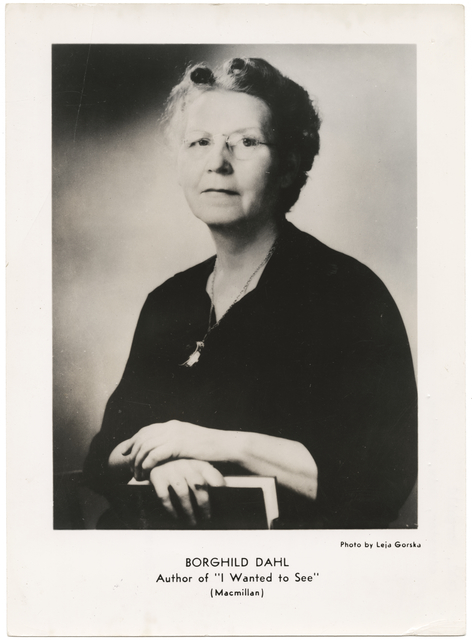

Borghild Dahl (1890-1984) was the author of many books, as well as a teacher, school administrator, and college professor. Her parents were Norwegian immigrants who had migrated to Minneapolis less than a decade before Dahl’s birth. Dahl used many of her children’s books to teach kids about the immigrant experience in Minnesota.

Dahl’s childhood was not easy. She was born in 1890 with severe vision impairments, and was blind by middle age. Even with her low vision, Dahl’s parents encouraged her to study and perform household chores. It was incredibly difficult for her to read books, and yet she loved it.

“I had to do all my seeing through one small opening in the left of the eye. I could see a book only by holding it up close to my face and by straining my one eye as hard as I could to the left,” she said. Even with these barriers, Dahl reported on school news—not for her high school’s paper, but for a major Minneapolis newspaper—at the age of 16.

Borghild Dahl went on to become a teacher, and eventually served as principal of 8 different schools in the region. She received her M.A. at Columbia and taught English at Augustana College in South Dakota for 13 years, largely from memory.

Borghild Dahl in 1950. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

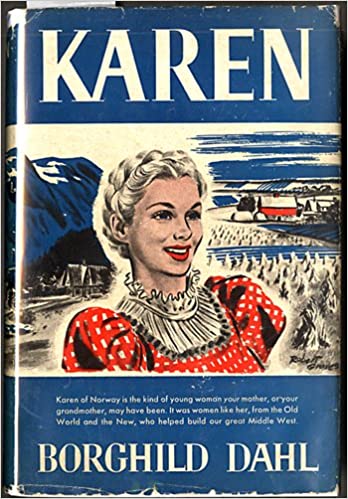

In addition to her robust teaching career, Dahl also found time to write 16 books. These books included a few autobiographical texts about Dahl’s experiences with blindness, including her most popular book, “I Wanted to See.” But Dahl’s time as a teacher must’ve taught her that everyone benefited by learning to celebrate diversity from a young age. She wrote most of her books specifically for children and teenagers. As the daughter of immigrant parents, Dahl was passionate about immigration and Norwegian culture, and used her books to teach these topics to young readers.

Her books shared many immigrant stories, ranging from the tale of a Norwegian family on the early frontier, to that of an orphaned Norwegian girl who was welcomed into an immigrant colony in America. She wrote of family, friendship, winter, and community.

Borghild Dahl’s children’s book “Karen.” Cover description reads, in part, “Karen of Norway is the kind of young woman your mother, or your grandmother, may have been.” Source: Amazon

When Dahl was 60 years old, she received the St. Olaf award from the King of Norway for building positive relations between the US and Norway. In 1980, at age 90, she received the Outstanding Achievement Award from the University of Minnesota. Dahl died in 1984 at the age of 94. She is buried in Lakewood’s Section 7.

Author and educator Mary Jackson Ellis (1916-1975) is largely considered the first full-time African American elementary school teacher in Minneapolis. Born in 1916, she was hired by the district at the age of 31 in 1947.

But her hiring was not without controversy: Ellis was initially denied the position as a classroom teacher due to her race. The story goes that Cecil Newman (owner of the influential Black newspaper the Minnesota Spokesman Recorder, who is also laid to rest at Lakewood) heard of this discrimination and immediately called then-mayor Hubert H. Humphrey (also laid to rest at Lakewood), who was a well-known advocate for civil rights. Together they went to the superintendent’s office and told the superintendent that Ellis would speak to the press about the discrimination she faced in the school system if she was not allowed to teach. The efforts of Ellis, Newman, and Humphrey were successful, and Ellis was hired.

Mary Jackson Ellis received a 1948 Certificate of Recognition from the magazine “Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life.” This magazine was an official publication of the National Urban League. Magazine digitized by Google Books.

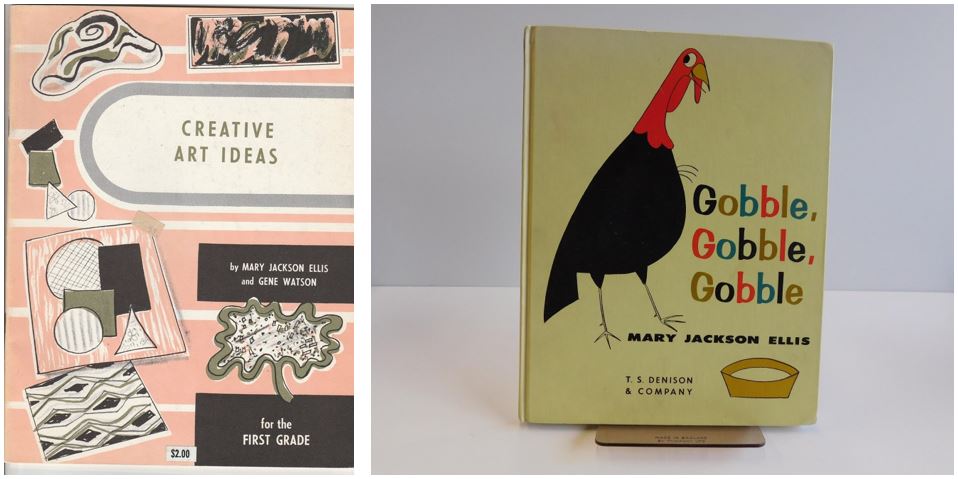

In addition to working in the Minneapolis Public Schools, Ellis also wrote children’s books and classroom guides. While her stories did not explicitly teach about diversity, she developed a series of guidebooks for educators that encouraged creativity among all young students.

Mary Jackson Ellis’ guides ranged from recommendations for kindergarten, first, and second grade classroom teaching and curriculum skills, to arts and crafts books. She also wrote popular local children’s books, including one called “Gobble Gobble Gobble” about a turkey who gets rescued by two children, and another about a character named ”Spaghetti Eddie.”

Two of Mary Jackson Ellis’ books, one fiction (for children) and one instructional (for educators). Sources: Abe Books and Etsy.

Many of Ellis’s books and instructional guides are still available today. Mary Jackson Ellis passed away in 1975, and is buried in Lakewood’s Section 60.

* * * * * *

Lakewood is grateful today, and every day, for the writers who have worked to ensure Minnesota children appreciate the diversity and creativity of our Minnesota community.