This month on our Facebook page, we’re honoring the nurses, caretakers, doctors, and researchers who have kept Minnesotans happy and healthy—from the frontier days to more recent years. All month, you’ll read the amazing stories of everyone from the abolitionist doctor who helped start Lakewood Cemetery, to the professional football player and dentist who used his immense knowledge of dentistry to help 9/11 disaster response teams identify the tragically deceased.

Drs. Orianna McDaniel, Alfred Elisha Ames, and Robert S. Brown

In today’s blog, we go deeper into the lives of three groundbreaking Minnesota doctors: Dr. Robert. S. Brown, the first Black doctor in Minneapolis, Dr. Orianna McDaniel, the first woman to work as a physician for the State of Minnesota, and Dr. Alfred Elisha Ames, one of the first physicians in frontier Minneapolis.

Robert S. Brown (1863-1927)

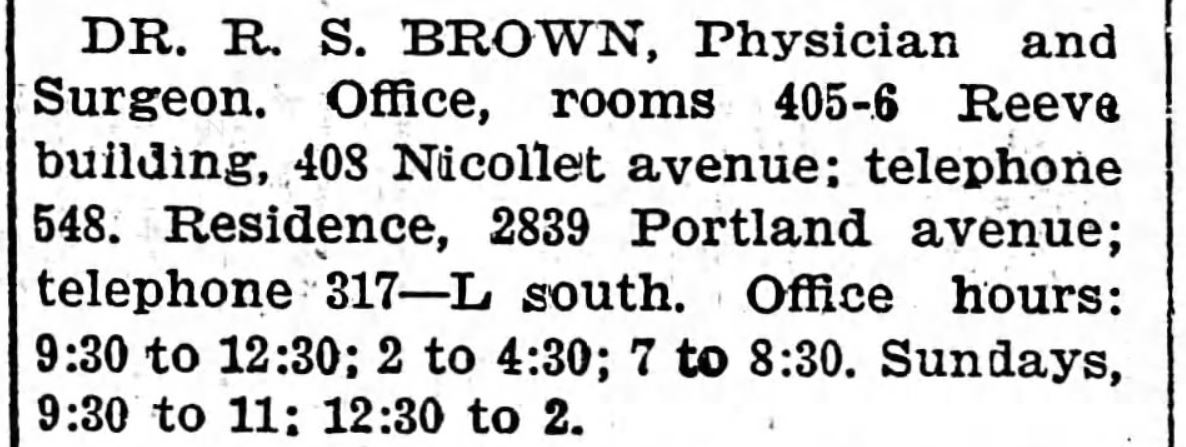

Dr. Robert S. Brown was the first Black physician and surgeon in Minneapolis. Born in Virginia in 1863, Brown graduated with honors from the renowned 19th-century Bennett Medical College in Chicago. Shortly after his graduation in 1895, Brown moved to Iowa, where he sustained a large practice before moving up to Minneapolis in 1898.

The Black community in late 1800s Minneapolis/St. Paul was small but thriving. At the heart of the community were anchors like churches and the local Black press. Owners and staff of the St. Paul-based newspaper The Appeal sought to grow the local Black community by placing ads promoting the Twin Cities’ residential and business opportunities in other Black-owned newspapers across the country. It is quite possible that Dr. Brown was recruited, in part, by this campaign to bring Black professionals to the Twin Cities.

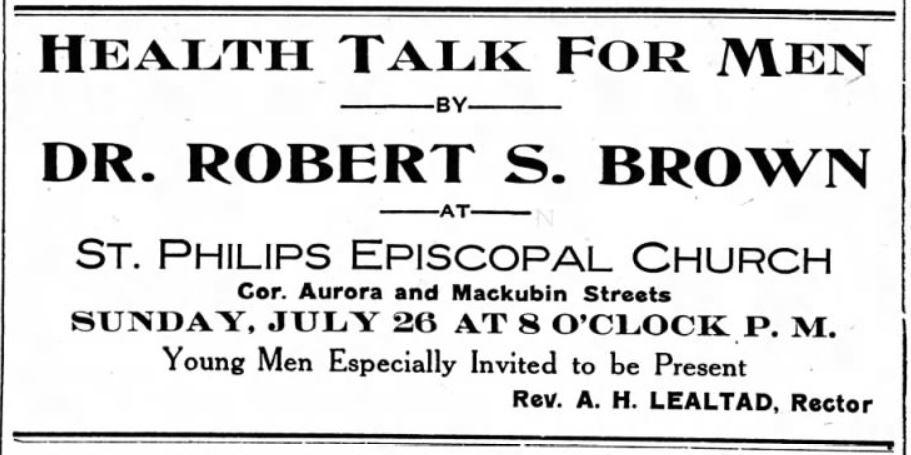

Once Dr. Brown arrived in the Twin Cities, the local Black press and community provided him immense support. Upon his arrival in Minneapolis, members of the community threw a large event at St. Peter African Methodist Episcopal Church to welcome Dr. Brown. The Appeal covered the event in detail. They even printed the text of the speech given by Dr. Brown, in which he applauded the community for supporting one another. In the years that followed, The Appeal continued to publish details of Dr. Brown’s life and practice.

In the speech that Dr. Brown gave upon his arrival, he expressed eagerness to get to know everyone in the room—and it seems that he did this in short order. In the speech, Dr. Brown gave out his home address and invited anyone to call on him at any time. He opened a medical practice downtown, where he saw patients seven days a week. He quickly rose to prominence, and was a part of many social groups and fraternal organizations, including the Elks, the Odd Fellows, and the Knights of Pythias. In 1921, he was elected president of the local chapter of the NAACP.

Having devoted himself to serving patients in Minneapolis for nearly two decades, Dr. Robert S. Brown died in his home on April 4th, 1927. He is memorialized in Lakewood’s Section 19. But his death did not mean the end of the Brown family’s service to patients. Robert S. Brown’s son and grandson followed in his footsteps, becoming doctors themselves. The Brown family served Minnesotans for three generations, until 1991.

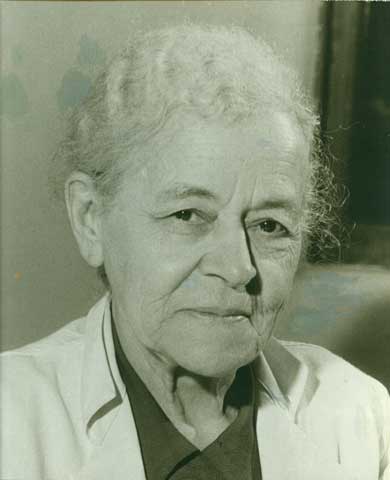

Orianna McDaniel (1872-1975)

Dr. Orianna McDaniel’s half-century career stretched from 1896 until 1946. McDaniel was the first woman to work as a physician for the State of Minnesota. She rose to prominence as the director of the State’s Division of Preventable Diseases. She was also a Clinical Associate Professor at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

Orianna McDaniel was born in Durham, North Carolina, in 1872. She was only 21 years old when she graduated from the University of Michigan’s medical school. McDaniel moved to Minneapolis in 1894 for her medical internship at Northwestern Hospital. Northwestern was one of the few hospitals that accepted women interns at the time.

In 1896, McDaniel began her career doing bacteriology laboratory work for the Minnesota Department of Health. At first she worked part-time, presumably due to the lack of opportunities available to women.

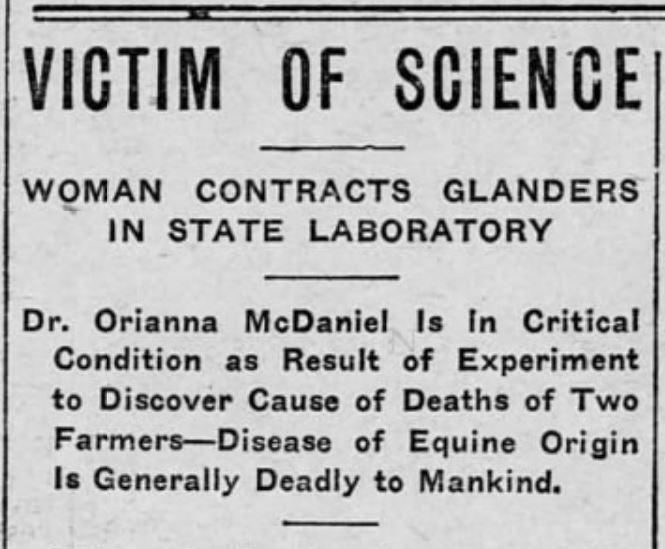

In 1902, she faced a near-death experience after becoming infected with a disease while researching it in the laboratory. The illness, called Glanders, was known to come from horses, killing even the mightiest of this species. The disease was very deadly to humans, and had already killed two men in Northwestern Minnesota. At the time of McDaniel’s illness, the newspapers wrote about the incident as though she was almost certain to die. “Victim of Science,” proclaimed one headline. “With death hovering near, Dr. Orianna McDaniel lies at her home in Minneapolis[,] the victim of her devotion to her profession,” it reads.

Thankfully, McDaniel recovered after being in critical condition. She returned to work and worked her way up in the Department. In 1921 she became head of the Division of Preventable Diseases.

McDaniel was with the Division of Preventable Diseases during a terrible smallpox outbreak in 1924. After the height of the epidemic, McDaniel was assigned to research and write a report detailing the causes of and responses to the outbreak. She wrote what is considered the most thorough and ambitious report on a smallpox outbreak ever taken on in Minnesota. She produced a 183-page assessment of the outbreak, in which she focused considerably on transmission in places like public hospitals and jails—sites where the poor and underserved were gathered, and where, it was deduced from her report, the Minneapolis Health Department failed to provide adequate vaccination resources. (St. Paul, on the other hand, had a more robust public health response and had significantly fewer deaths.) Most of what we know about the 1924 smallpox epidemic in the Twin Cities comes from McDaniel’s report.

Orianna McDaniel worked until she was 74 years old, retiring in 1946. But despite working into old age, McDaniel proved to have a long life ahead of her. She spent nearly three more decades living at her home on 44th & Grand before moving to a home for the aging. McDaniel passed away in 1975 at 102 years old.

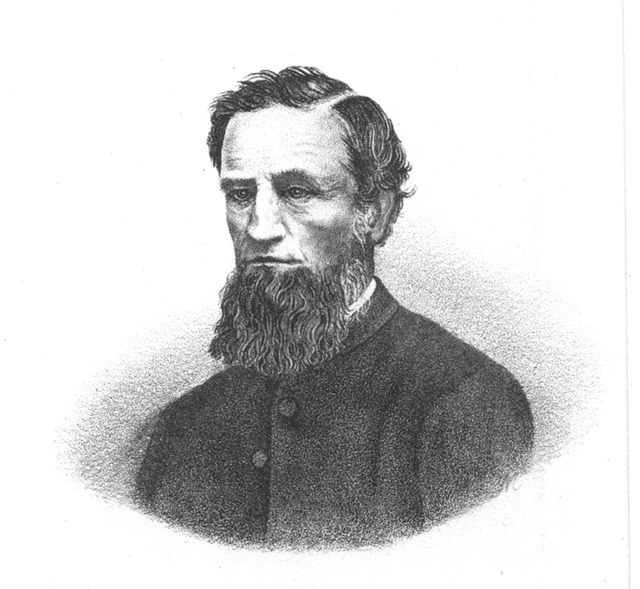

Alfred Elisha Ames (1814-1874)

Alfred Elisha Ames was one of the first doctors in Minneapolis, practicing medicine when the city was just a small frontier community.

Alfred Elisha Ames had a robust career before moving to the small frontier town that we now call Minneapolis. Born in 1814 in Vermont, he moved to Ohio as a teenager. Five years later, he moved to Illinois, where he started a long political career. There he served as deputy secretary of state, and eventually served in the Illinois House of Representatives. All the while, Ames found time to attend medical school, graduating in 1845.

When Ames came to Minnesota in 1852, the territory was still six years away from officially becoming a state. The Twin Cities were small, remote outposts. Yet Ames gave up his comfortable political career to face the unknown. He settled in St. Anthony, now Northeast Minneapolis, and immersed himself in life here. He became the area’s first civilian doctor. He also founded the area’s first Masonic temple. And just two years after his arrival, Ames was elected to the Minnesota Territorial House of Representatives. He went on to become Minneapolis’ first postmaster, and served on the school board.

In addition to his robust political career here in Minnesota, Ames also maintained a medical practice. Like other doctors in the early frontier days, Ames primarily worked alone, without the support of a large hospital system. But Ames also saw the limitations of this isolated approach to medicine. He co-founded both the Minnesota Medical Society and the Hennepin County Medical Society, both of which sought to bolster public health, improve patient experiences, and grow the professional medical community in the burgeoning frontier territory. In 1871, the same year Minneapolis officially became a city, Ames co-founded St. Barnabas Hospital for the poor on the edge of downtown Minneapolis.

Ames practiced medicine until late in life. He died on Christmas Eve of 1874. His son, Albert Alonzo Ames, also studied medicine, and served as mayor of Minnesota. Alfred Elisha Ames is buried with his wife Martha in Lakewood’s Section 3.

A Thank You to our Medical Professionals

Today and everyday, Lakewood is grateful to the medical professionals who work tirelessly to keep us and our neighbors healthy—from 19th century frontier doctors, to the nurses, doctors, and caretakers on the front lines of the Covid-19 pandemic today.