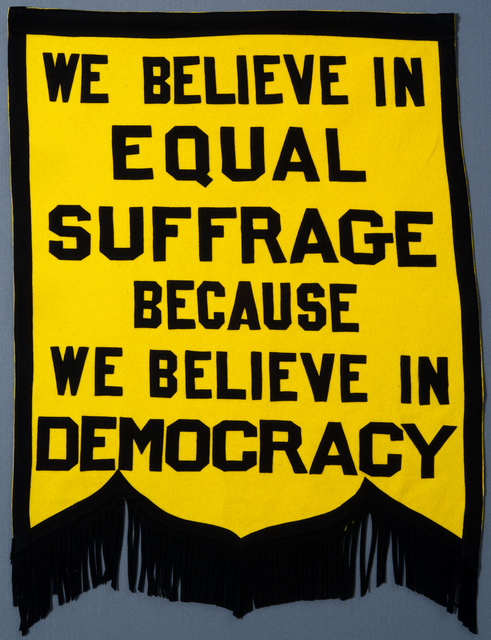

A suffrage banner from 1913 St. Paul. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Clara Ueland was born in 1860 to a working class family in Ohio. Her father died when she was quite young, and her family moved to Minneapolis in 1869. From an early age she showed a proclivity for independence and equality, living her life according to feminist principles. As a young woman she worked as a school teacher in Minneapolis. After she married a Norwegian immigrant and lawyer named Andreas Ueland, she turned gender norms on their head by encouraging her sons to do housework and supporting her daughters in their paths toward higher education. (One of her daughters, Brenda Ueland, went on to become a prominent writer.) While raising eight children, she made time to pursue a greater social good, establishing a number of free kindergartens across Minneapolis.

Women had been organizing for the right to vote since the 1860s. But it wasn’t until 1901, when Ueland was about 40 years old, that a local women’s conference inspired her to get involved in the women’s suffrage movement. In 1915 she became the president of the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association, the most prominent suffrage organization in the state. She worked with women—urban and rural, Black and white—to push for the vote. She eventually became the first president of the Minnesota League of Women Voters. Her journey toward suffrage was a long one, but once she set her mind on voting, she could not be stopped.

Clara Ueland. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

An Imperfect Amendment: Suffrage and Segregation

Clara Ueland was 60 years old on August 26, 1920, when the 19th Amendment went into effect. For the first time, women of European descent would be allowed to vote in every state and federal election.

The amendment was far from perfect. In practice, the women’s suffrage did not benefit all women: it would take another 32 years before many voting restrictions were lifted for Asian Americans, 42 years before Native Americans were granted voting rights in every state, and 45 years before the Voting Rights Act of 1965 helped secure voting rights for Black Americans and other members of Indigenous and People of Color communities.

Before the amendment went into effect in 1920, women of many different races and ethnicities organized for women’s suffrage all across the country. But though women of all races were advocating for the right to vote, the right, in practice, was extended mostly to white women. Across the country, and here in Minnesota, suffrage organizations were overwhelmingly segregated by race. Groups like the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association had only white members. Women’s organizations that weren’t specific to suffrage were segregated, too. (There was, for example, a Minnesota Federation of Women’s Clubs, and a Minnesota Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs.) This segregation was something that many Black women, and some white women, in Minnesota had fought against. But many white women pushed for the racist status quo.

In 1914, Clara Ueland rose to prominence in the Minnesota Women’s Suffrage Association. That same year, another suffrage group was formed in St. Paul. It was called the Everywoman Suffrage Club, and it was made up of 25 prominent Black women in St. Paul.

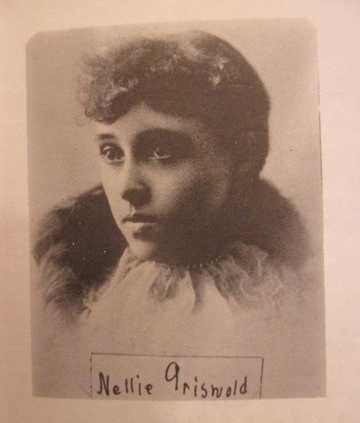

Nellie (Griswold) Francis’ 1891 St. Paul High School graduation photo. The only Black student in her graduating class, Francis gave a speech about racism at her graduation, and was met with resounding applause. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

The club, whose motto was “Every woman for all women and all women for every woman,” was started by Black women’s rights activist Nellie Griswold Francis. Francis, who was born in 1874 in Tennessee and was the only Black student in her graduating class at St. Paul High School, had been speaking out against racism and organizing in support of Black churches and groups since she was a teenager. Before starting the Everywoman Suffrage Club, Francis had already made the acquaintance of both President Taft and Andrew Carnegie.

Clara Ueland was blown away by Francis’ work. “Mrs. Frances [sic] is what we call a ‘lady,’ but her spirit is a flame,” Ueland once said. The two began collaborating, and the Everywoman Suffrage Club sent representatives to the Minnesota Women’s Suffrage Association’s conventions.

Though they both ran suffrage groups that were exclusively open to women, Ueland and Francis also advocated for women and men to work together on women’s suffrage and women’s rights issues. Nellie Francis’s organization’s mission explicitly advocated for collaboration between genders and races. In her publications to the statewide Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association, Clara Ueland told women how to persuade men to vote for suffrage; after all, women could not cast ballots in favor of their own rights.

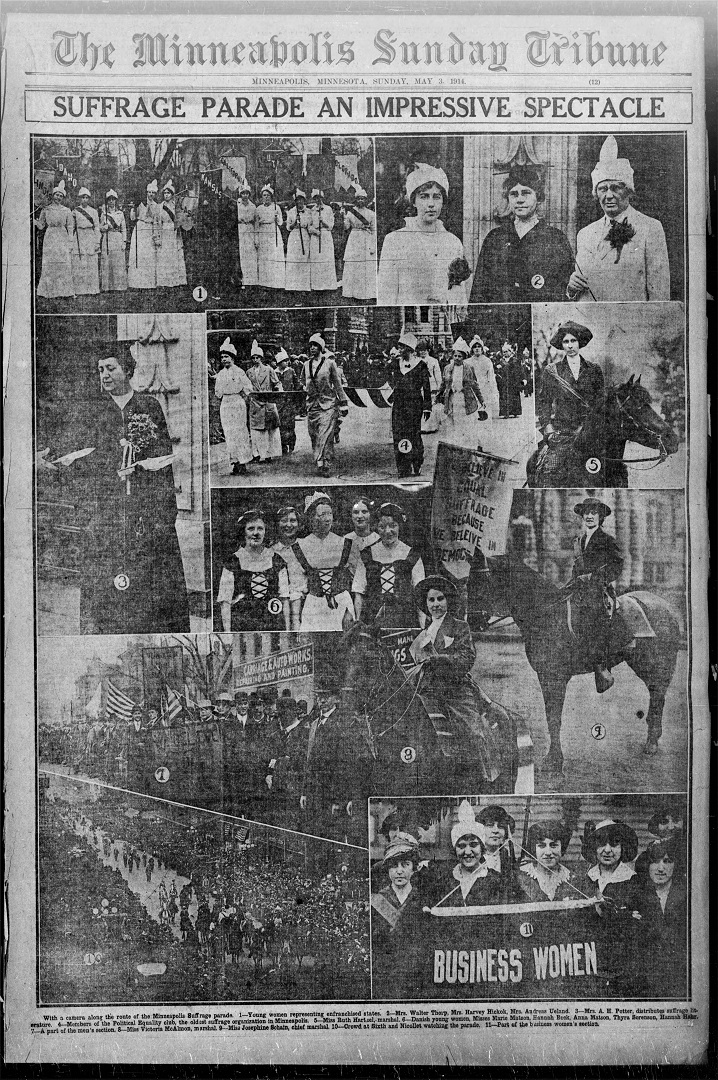

A group of Scandinavian suffrage advocates marches in a 1914 parade. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

A March Toward Victory

As the 1910s bore on, Clara Ueland became more and more vocal about women’s suffrage. In 1914, she organized a huge suffrage parade that is often credited with renewing (or initiating) many Minnesotans’ interest in women’s suffrage. Through her expert combination of advocacy, publicity stunts, mail campaigns, speeches, organizing, and the collaboration of Minnesota’s Black suffragists, Ueland advanced the cause of suffrage in Minnesota. Ueland made a special outreach effort to those outside of the Twin Cities, who were often less supportive of suffrage. One Minnesota suffragist leader called her “the Moses who is leading Minnesota to the promised land.”

Images from the 1914 suffrage march. Source: Minneapolis Tribune via Newspapers.com

When Governor J. A. A. Burnquist signed women’s suffrage into law, he gifted the signing pen to Clara Ueland. And an article in the Minneapolis Journal suggested that it was largely thanks to Ueland’s leadership that suffrage was passed in Minnesota.

Suffrage Is Not Enough

Clara Ueland remained a political firebrand after the 19th Amendment became the law of the land. After suffrage, Ueland shifted her focus to advocating for child labor laws, pushing for protections for young workers. All the while, she remained involved in campaigns to increase women’s political engagement.

Clara Ueland was tragically killed at age 66 in 1927. She was on her way home from the State Capitol where she had been campaigning for child labor laws when she was hit by a truck near her home.

In honor of this centennial of women’s suffrage, you can pay your respects at Clara Ueland’s grave in Lakewood’s Section 9.

Clara Ueland’s grave at Lakewood

A few notes

- After the 1920’s implementation of women’s suffrage and the horrific lynching of three Black men in Duluth that same year, Nellie Francis became a vocal anti-lynching advocate both locally and nationally. Her husband, prominent lawyer W. T. Francis, became the first Black Minnesotan diplomat. The two went to Liberia during Mr. Francis’ position as U.S. Minister and Consul. W.T. Francis died while they were in Liberia, and Mrs. Francis moved to Tennessee to take care of her 100-year-old grandmother. Francis herself lived to be nearly 100, and is buried in Tennessee.

- Across the country, indigenous women fought for the right to vote. But it wasn’t until 1924 that voting rights were extended to some Native people, and not until 1962 that the last state (Utah) lifted Native voting restrictions. To learn more about the role of indigenous women in the suffrage movement, check out this New York Times article.

- Special thanks to Gustavus Adolphus College’s Misti Harper for her research on interracial suffrage organizing in Minnesota.