In the early days of Minneapolis, getting from Point A to Point B wasn’t so easy. There were no cars, and horse-drawn carriage rides were expensive. Roads were not maintained by the city. They were paved with stones only at the motivation of the individual property owners; some property owners surfaced their roads with wood slats, but most roads were just dirt (or mud, when it rained). This made foot travel dependent on the weather. Even for those who could afford carriage rides, the uneven terrain was hard on the horses. In today’s blog, we tell the stories of the businesspeople and engineers who helped create the earliest publicly-accessible transportation in the young city of Minneapolis: from ferries, to horse-drawn streetcars, to electric trolleys.

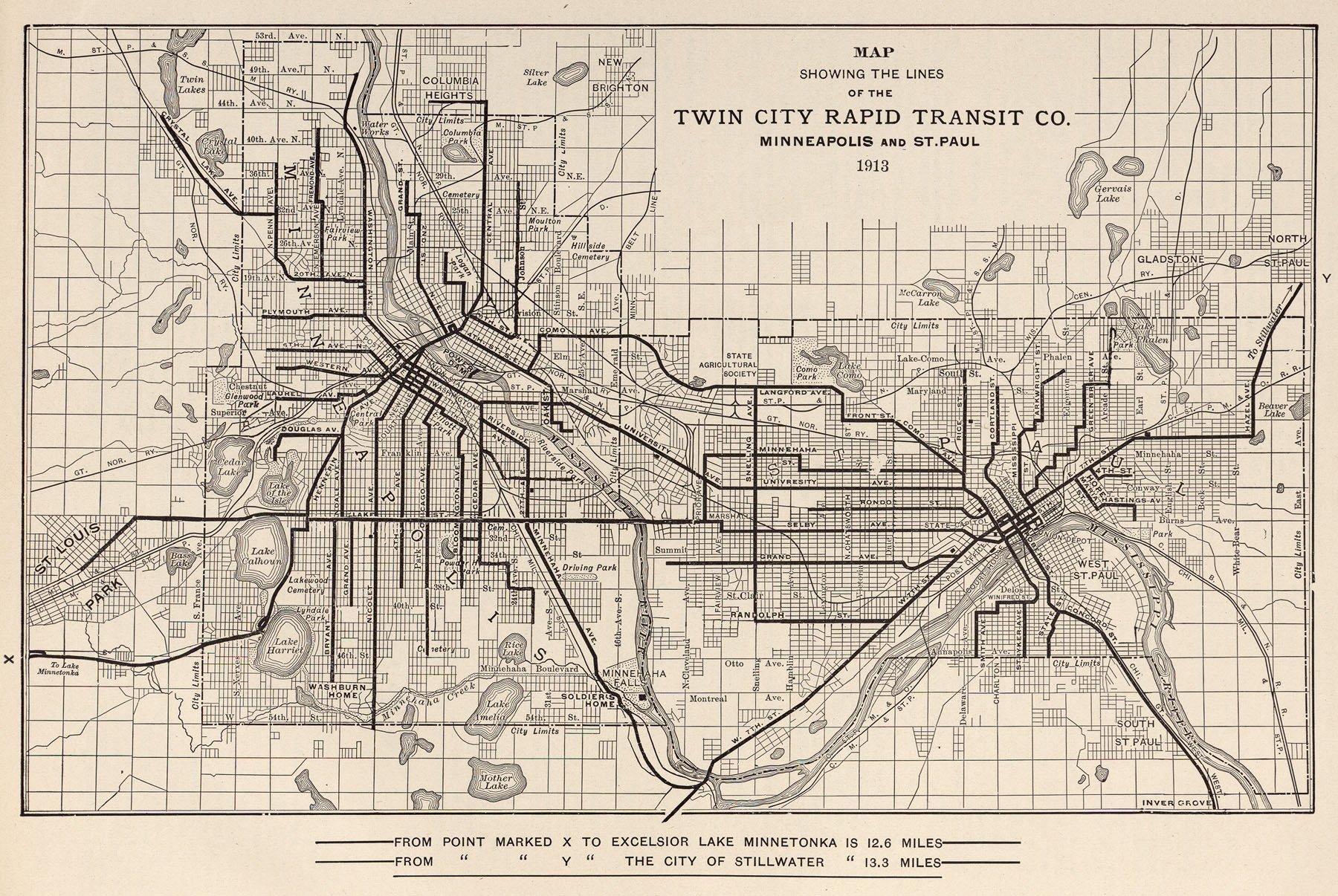

A 1913 map of the Twin Cities streetcar system. Source: Reddit

The Earliest City Streets

Beginning in the late 1830s, white colonists began a settlement on the East Bank of the Mississippi river in what we now call Northeast Minneapolis. Drawn to the industrial potential of St. Anthony Falls, they called their village St. Anthony. This original settlement predated the city of Minneapolis by many years. A small smattering of stores, and eventually hotels and mills, dotted the riverfront along Main Street, a cobblestone road originally built in 1840.

In 1850, a settler named John H. Stevens built what is largely considered to be the first wood frame home built on the west bank of the Mississippi in what soon became Minneapolis. Stevens was granted permission from the army to settle on the land now occupied by the downtown Minneapolis branch of the Post Office. The land was under the auspices of the army, because by this time colonizers had claimed ownership over much of the land surrounding the river as part of the Fort Snelling Military Reservation. The Fort itself had been established over three decades prior on land originally claimed as part of an 1805 treaty between Army Lieutenant Zebulon Pike and Dakota leaders. However, the treaty was not authorized by the US government, and only a fraction of the indicated amount was paid to the Native people. Despite the unauthorized and incomplete nature of the treaty, it laid the groundwork for the development of what became Fort Snelling. Decades later, when Stevens wanted to construct his home on the river’s west bank, the army permitted this development in exchange for Stevens personally operating a ferry service from St. Anthony on the east bank, to the new development of Minneapolis on the west bank.

The John H. Stevens House was moved to its present-day location atop Minnehaha Park in 1896. Source: Wikimedia

Four years after Stevens finished his home, the young frontier outpost of Minneapolis was starting to grow. A small network of dirt roads were mapped out, forming a grid of streets that ran along a small section of the Mississippi River. The earliest town development followed Hennepin Avenue, which had been built following a Dakota footpath that connected two sacred sites: Bde Maka Ska and Owámniyomni (St. Anthony Falls). By the middle of the decade, a suspension bridge connected St. Anthony to Minneapolis. By this time, there were around 100 houses in the small settlement of Minneapolis.

Horse-Powered Streetcars: Serving the Masses

As Minneapolis grew, the need for street maintenance and transportation became obvious. By the early 1870s, many large cities across the country offered some sort of transportation that was accessible to the masses. Something had to be done if the Twin Cities wanted to keep up.

For the first nearly century of “public transit,” the vehicles that made Minneapolis move were not, in fact, public. Like other burgeoning cities, transit was a private enterprise. (New York City’s early train and subway lines, for example, were owned by multiple different companies, before the system was consolidated under the city’s authority in 1968.) So in 1872, businesspeople in neighboring St. Paul took a cue from other cities like New York and Chicago, both of whom had robust networks of horse-drawn streetcars.

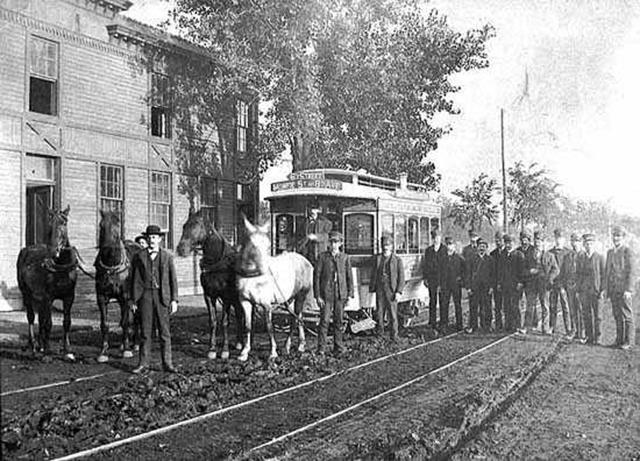

A St. Paul Streetcar in 1875. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Though pulled by horses, these “horsecars” ran along tracks, just like trains. The cars were small—about 10 feet long, weighing roughly the weight of one horse, and able to accommodate 14 passengers. The interior was lined with hay in the winter for warmth. The horsecars could go up to six miles per hour.

Horse-drawn streetcars were far from perfect: the cars would sometimes jump the tracks and tip over, requiring the passengers to set them upright and put them back on the tracks. Sometimes passengers had to get out of the car and help push the unit up hills when the horses were tired. But even so, the horsecars were an improvement over walking.

Minneapolis wanted a piece of the pie, too. In 1875, the City Council wanted to encourage the development of the horsecars. The City reached a deal with the newly-formed Minneapolis Street Railway company: the young company could have exclusive control over street-level transit in Minneapolis for 50 years if they were able to set up a horsecar system within four months. The young company knew just the businessperson who could help them make it happen.

Businessman Thomas Lowry in 1902. Source: Wikimedia

The company tapped Thomas Lowry. Thomas Lowry had made a name for himself as a real estate developer. He originally arrived in Minneapolis in 1867, without much money, to work as a lawyer. But within two years he had switched career paths. He saw that Minneapolis was growing rapidly, and bought properties that were quickly subsumed into city limits as Minneapolis grew.

Lowry was a keen businessman. Not only would his service benefit the people of Minneapolis, but it would also be a good financial decision: many of his real estate holdings were on the edge of the city, and if he could provide transportation to them, they would be more valuable. He jumped at the opportunity. And in September of 1875, the first Minneapolis horsecar line opened, connecting downtown to the University of Minnesota. Three years later, Lowry was president of the Minneapolis Street Railway company.

Horses and Steam Trains and Trolleys, Oh My!

Horse-powered streetcar lines ran throughout the 1870s and 1880s. The horsecars ran all the way to the edges of both Minneapolis and St. Paul. An average of 1,700 daily passengers paid five cents for their journeys. But the horsecars were difficult to maintain. Horsecar stations needed to have not just a mechanic on hand, but a full stable, and a blacksmith, too. And the horse excrement was posing a health hazard.

A Twin Cities horsecar. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Some other railway companies tried to step in and provide other transit options to Twin Cities residents. In 1879, the Lyndale Railway Company started offering a steam engine service from downtown Minneapolis, past Bde Maka Ska, and up to Lake Harriet. While scaled-down steam engines had been used for short-distance travel in cities like New York and Chicago, the technology was mostly reserved for long-distance travel and freight delivery. The trains were noisy and smokey. They were known to frighten the horses that traversed the streets and pulled both personal carriages that publicly-accessible horsecars along their tracks. The steam engine wasn’t popular for short journeys within the Twin Cities.

In the late 1880s, St. Paul briefly experimented with cable cars. With its more hilly landscape, St. Paul took a cue from San Francisco, who had been using cable cars for 15 years. While they could go up to a whopping 10 miles per hour, the steam-powered cable cars were a hard sell in St. Paul. They were dangerous (one cable car jumped the track going down a hill in St. Paul on the first day of operation, tragically leaving many people injured and one dead). The lines were also costly to build, and build-ups of snow and ice on the cables made them difficult to maintain—not to mention produced anxiety about possible snaps, which would shut down the whole system.

The “Tom Lowrys” Go Electric

In the late 1880s, the recent development of electrification brought new possibilities to the Twin Cities. Before fall of 1882, the city was lit primarily by dim gaslight. But on September 5th, portions of downtown Minneapolis’s Washington Avenue were illuminated with electric lights, powered by a waterwheel just below St. Anthony Falls. Over the next several years, electricity gained popularity around the city.

On Christmas Eve, 1889, Minneapolis’s first electric trolley debuted. It was a success. Thomas Lowry, who had gained control of the St. Paul transit lines three years prior, began converting his Twin Cities fleet to electric power. By 1892, all of Lowry’s fleet was converted to electric power. Electric streetcars, which were also called “Tom Lowrys,” made the Twin Cities move.

Civil engineer William De la Barre. Source: MNopedia

In the 1890s, the Twin Cities were growing, and so was its electricity consumption. In 1895, a civil engineer from Austria named William De la Barre started working on a large new power generating project to keep up with the demands of the growing population. De la Barre had already made a name for himself as director of the Minneapolis Mill Company. The Minneapolis Mill Company generated power from St. Anthony Falls. De la Barre didn’t just oversee this process, but he made many improvements upon it. In 1895, he began building the million-dollar Lower Dam and Lower Dam Hydro Plant below St. Anthony Falls. Completed two years later, the land was immediately leased by Lowry and Twin City Rapid Transit Company to power more of his electric cable cars. This was the start of a mutually beneficial relationship; De la Barre later opened an electric plant on Hennepin Island, which was also used to power the electric streetcars.

The Rise and Fall of Streetcars

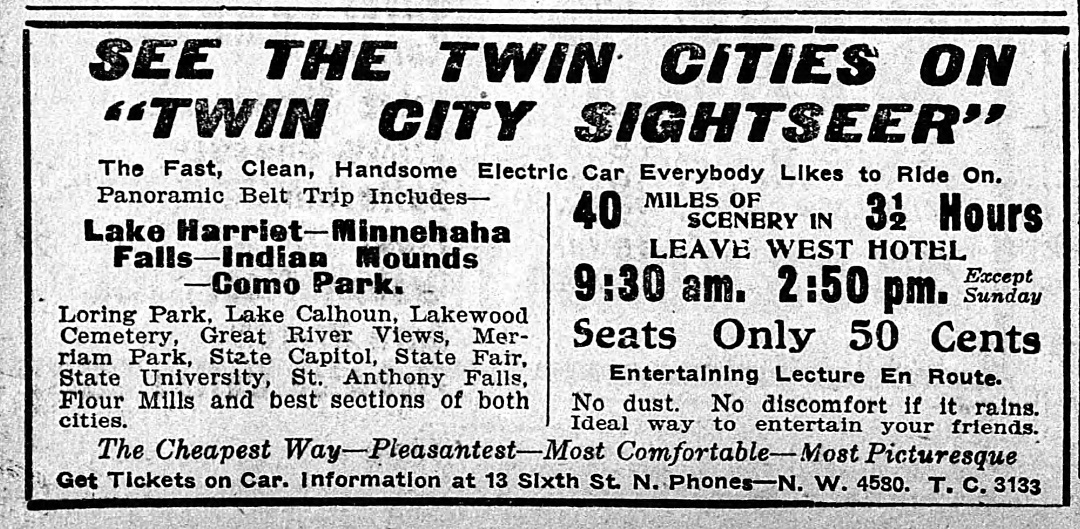

The trolleys were the main form of transportation in the Twin Cities throughout the first half of the 1900s. By 1906, the streetcar could bring you to Lake Harriet, Loring Park, across the Mississippi River Gorge, to the State Fairgrounds, and even to two different amusement parks, one off of Lake Street in Minneapolis and one on White Bear Lake. The streetcars weren’t just an efficient way to get around. The cars were also an attraction in and of themselves. Many of those attractive destinations were featured on the “Twin City Sight Seer” trolley tour. Guests would pay 50 cents to spend three and a half hours covering 40 miles across the Twin Cities, entertained all the while by a lecturer.

A 1906 ad for the Minneapolis Sightseer. Source: Minneapolis Journal via Newspapers.com

In 1920, streetcar ridership peaked at an impressive 238 million passengers. That decade, Lowry’s consolidated Twin City Rapid Transit Company ran 900+ cars on more than 520 miles of track. But the growing accessibility of personal automobiles meant that the streetcars were less popular by the 1930s.

All over the country, streetcar use dropped off significantly after World War II. Automobiles became more popular, the suburbs were growing rapidly, and busses were eyed as the future of public transit. Across the Twin Cities, fixed streetcar lines were replaced by more adaptable bus routes. The last streetcar was removed in 1954. Today, one section of the historic Como-Harriet streetcar line remains. This line, which started on the west side of Lake Harriet and terminated at Como Park, still runs right along the western edge of Lakewood. Today, you can still see Lakewood’s former streetcar entrance at that location.

The Como-Harriet streetcar line in the present. Source: Wikimedia

The Minnesota Streetcar Museum, which operates the historic line, is taking a break from service due to Covid-19. But when transit renews, you can ride the trolley from Lake Harriet to Lakewood Cemetery and back again. And as you sit in the train, you can imagine yourself in 1906, paying 50 cents for the Twin City Sightseer to take you past Lakewood.

Visit the early transportation leaders mentioned in this blog

Thomas Lowry, Section 6

John Harrington Stevens, Section 27

William De la Barre, Section 7