In February we honor both President’s Day and Black History Month. No U.S. presidents are buried at Lakewood. But Lakewood does serve as the final resting place of Vice President Hubert Humphrey, as well as many African American leaders who helped shape Humphrey’s stance on civil rights. In this blog post we explore the lives and legacies of just a few of these leaders.

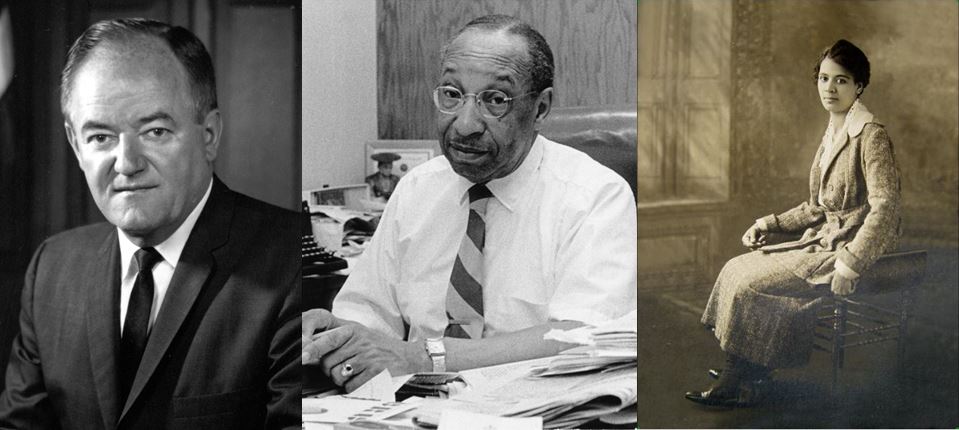

Hubert H. Humphrey, Cecil E. Newman, and Lena O. Smith

Born to a working class family in the small town of Wallace, South Dakota in 1911, Humphrey became involved in local politics shortly after moving to Minneapolis for graduate school. Financial difficulties forced 29-year-old Humphrey to drop out of his doctorate program and work for the WPA, where he was eventually responsible for placing Minnesotans at wartime job sites. This position, combined with his personal struggles with poverty and the recent memory of the Great Depression, solidified Humphrey’s belief in the value of fair employment opportunities. Local black-owned newspapers began to recognize Humphrey as an ally, as Humphrey supported African Americans and whites equally in his attempt to bring employment to Minnesotans.

In 1943, members of Minneapolis’s progressive Farmer-Labor Party encouraged Humphrey to run for office. He received the endorsement of local black-owned newspaper the Spokesman Recorder. Humphrey had only lived in the city for a few years, but he only lost by the small margin of just under 6,000 votes. The people of Minneapolis were beginning to see the potential of the man who would go on to serve many terms as State Senator, help draft the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and ensure the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (which finally extended the right to vote to African Americans).

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Humphrey

In 1945, Humphrey ran again for mayor, this time winning by a landslide. At 34 years old, he became the city’s youngest mayor at the time. As mayor, he passed the country’s first municipal Fair Employment Practices Commission law, which helped limit bias in employment. He also formed political advisory groups, to which he appointed members of the African American, Jewish, and Indigenous communities. Many of his programs were innovative, even on a national scale. By 1948, Humphrey secured a place for himself on the national stage by delivering a time-honored, historic speech about going “into the bright sunshine of human rights” at the Democratic National Convention. Many people credit the Democratic Party’s adoption of a human rights platform to Humphrey’s speech.

But Humphrey’s progressive, human rights-focused platform did not appear out of nowhere. In 1930s and 1940s Minneapolis, discrimination was a pervasive experience for the city’s small but growing African American population. Though local legislation said that social services could not be legally denied based on race, discrimination was still widespread; tactics like restrictive covenants and employment bias meant there were significantly less opportunities for blacks than whites. In the 1940s, many of the city’s fine hotels and restaurants refused to serve black patrons. It was in this context that members of the local black community had been forming advocacy groups and unions, social organizations, as well as their own restaurants, hotels and businesses. Recognizing the decades of organizing taken on by these African American residents, Mayor Humphrey deferred to their experience, and often brought in local African American leaders for guidance.

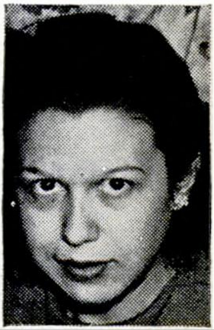

Lena Olive Smith

One of the local African American leaders most influential to Humphrey was Lena Olive Smith. Lena Olive Smith was the first African American woman lawyer in the state of Minnesota. Throughout her life she used the courts and other activist strategies to fight tirelessly for civil rights. Together Smith and Humphrey worked to combine the state’s liberal Farmer-Labor Party with the Democratic Party, creating the Democratic-Farmer-Labor (DFL) Party in 1944.

Lena Olive Smith. Source: Star Tribune

Lena Olive Smith. Source: Star Tribune

Smith and Humphrey also worked with African American activist and union organizer Nellie Stone Johnson to merge the Democratic and Farmer-Labor Parties. Johnson worked closely with African American union organizer Anthony Brutus Cassius to organize Hotel and Restaurant Workers Local 665. Cassius himself owned a restaurant that served many prominent black performers and activists when they were turned away from other restaurants in the city. Cassius is buried in Lakewood’s Section 55. Though Cassius did not work directly with Humphrey, his influence was indirectly felt through Humphrey’s close alliance with Nellie Stone Johnson and Lena Olive Smith.

Lena O. Smith was born in 1885. She grew up in Lawrence, Kansas, and moved with her family to Minneapolis in 1906. In Minnesota, Smith had many careers–she instructed drama, went to embalming school, opened a salon, and worked as a realtor all before becoming a lawyer. As a realtor, Smith saw firsthand how home sales and restrictive covenants were used to enforce racism and segregation in Minnesota. It was these discriminatory practices that led Smith to take night classes at law school.

Smith graduated from law school at age 35 and filed her first suit 11 days after graduating. She sued a white property owner for illegally refusing to sell a home to an aging black couple. Years later, she famously defended a black WWI veteran and his family when a mob of nearly 4,000 gathered outside their home to protest their move into an all-white Minneapolis neighborhood. She successfully sued for equal accommodations and integration at local businesses, and defended African American residents who had been victims of police and civilian violence.

Smith fought for civil rights outside of the courts, too. She helped found the Minneapolis chapter of the Urban League, served as the first woman president of the Minneapolis NAACP, and expertly maneuvered politics and the press to ensure the work she fought for in the courts would stick. She advocated for mass protest, spoke at rallies, and gave lectures about racial discrimination across the city.

Smith’s influence was held in high regard by Humphrey. She was invited to the Lyndon B. Johnson / Hubert Humphrey inauguration in 1965. Lena Olive Smith passed away the following year, and is buried in Lakewood’s Section 22.

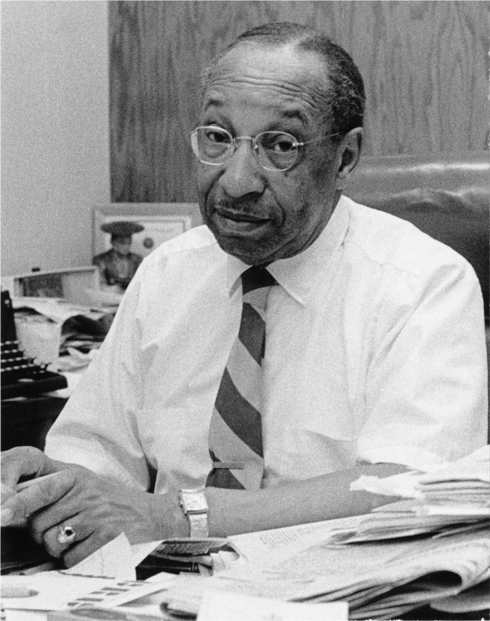

Cecil E. Newman

Cecil E. Newman was another leading African American organizer in 1930s/1940s Minneapolis. He founded the Minneapolis-based Spokesman Recorder, one of the state’s most prominent black-owned newspapers. Through his paper, he endorsed Humphrey’s 1943 and 1945 campaigns for mayor. He influenced Humphrey directly by serving on the mayor’s Council on Human Relations.

Cecil Newman used the power of the press, as well as engagement with local politics, to advance civil rights in the Twin Cities. He belonged to more than 40 professional and civil rights groups, including the NAACP and the Minneapolis Urban League, and served as the first African American member of the Minnesota Press Club.

Cecil Newman, founder of African American Newspaper the Minnesota Spokesman Recorder. Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Newman was born in 1903 in Kansas City, Missouri, where he was a neighbor of future poet Langston Hughes. With his parents’ encouragement, Newman developed a passion for journalism early, working in the back office of a black‐owned newspaper while in high school, and submitting content about bias in employment (an issue close to Humphrey’s heart). He moved to Minneapolis shortly after high school, where he contributed to the local black press and founded his own newspaper and magazine.

Though many media outlets struggled through the Great Depression, Newman was rightfully convinced that African American Minnesotans could sustain their own media network even in difficult economic times. Amidst the Depression, Newman was able to quit his job as a porter to focus on journalism, and in 1934 founded the enormously successful Spokesman Recorder, which still operates today.

The Spokesman Recorder took a firm stance in support of civil rights. Newman himself worked closely with many politicians, including both Mayor and Senator Humphrey. The Spokesman Recorder’s editorials were used to keep politicians accountable, advance the causes of integration, and promote demonstration against local businesses practicing discrimination.

Newman worked actively until his death in 1976. Newman’s legacy lives on in the continued weekly publication of the Minnesota Spokesman Recorder, and as the namesake of Cecil Newman Plaza in North Minneapolis, the Cecil E. Newman Scholarship for African American college attendance, and Cecil Newman Lane in South Minneapolis.

Mary Jackson Ellis: Leaders Combine Their Influence

Mary Jackson Ellis is largely considered the first full-time African American elementary school teacher in Minneapolis. Ellis was hired by the district in 1947 at the age of 31. But her appointment was not without controversy. The story goes that it was thanks to the combined effort of Ellis, Cecil Newman and Hubert Humphrey that she was hired at all.

Mary Jackson Ellis, 1955. Source: Jet Magazine

The district initially denied Ellis a position as a classroom teacher due to her race. When Cecil Newman heard of this discrimination he immediately called then-mayor Hubert H. Humphrey. Together Humphrey and Newman went to the superintendent’s office. They informed the superintendent that Ellis would speak to the press about the discrimination she faced in the school system if she was not allowed to teach.

Ellis, Newman, and Humphrey’s combined efforts were successful. Ellis was hired as the Minneapolis school district’s first full-time elementary school teacher. Ellis went on to have a very influential career in teaching. In addition to her work in the classroom, she published multiple children’s books and teaching aids that are still available today. The Hale School, where she instructed, grants the Mary Jackson Ellis award to outstanding fourth-grade students every year. Mary Jackson Ellis passed away in 1975, and is buried in Lakewood’s Section 60.

* * * * *

We express our deep appreciation for Lakewood residents Hubert Humphrey, Lena Olive Smith, Cecil E. Newman, Anthony Brutus Cassius, Mary Jackson Ellis, and countless other leaders who have made this city, state, and country more equitable.