July is a special month in Lakewood’s history. This month in 1871, local leaders began laying plans for the cemetery. A nonprofit since its founding, it all began when then-mayor Dorilus Morrison called together a group of early Minneapolis business and civic leaders to discuss plans for a large, park-like cemetery. It was the first grand, garden-style cemetery in the area.

But Lakewood was not the first public cemetery in what is now the city Minneapolis. Beginning before graveyards for settlers were built, Native populations constructed hundreds of collective burial mounds across what became the metro area, often on the area’s most practical and breathtaking vistas. Beginning in 1851, two primary public graveyards served the city’s booming and diverse settler populations. Today these two cemeteries remain important to our city’s history. One site, now known as Pioneers & Soldiers Cemetery, serves as a historic destination in South Minneapolis. The other is better known as Northeast Minneapolis’s Beltrami Park.

Today’s blog post explores the history of these graveyards to better understand why city leaders felt compelled to create Lakewood Cemetery.

The backstory: St. Anthony and early Minneapolis

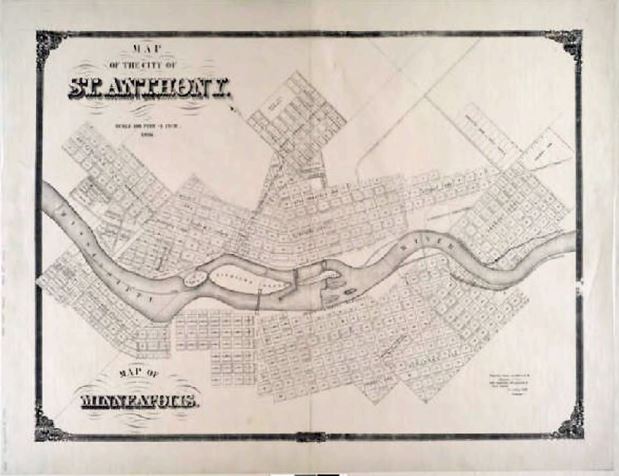

When settlers first arrived in the region, they settled mostly on the east bank of the Mississippi River. Though we now call this area Northeast Minneapolis, it was originally named St. Anthony. St. Anthony got its start in 1838 when Fort Snelling storekeeper Franklin Steele claimed the land on the east side of St. Anthony Falls. He began developing the city ten years later. St. Anthony quickly became a hub for milling, shipping, and logging. Then, in 1850, John Harrington Stevens (also buried at Lakewood) became the first settler to build a permanent frame house on the west bank of the river, beginning a settlement that came to be known as Minneapolis.

An 1856 map of the towns of Minneapolis and St. Anthony (now Northeast Minneapolis).Source: Hennepin County Library

Like other frontier towns, the populations of St. Anthony and Minneapolis grew exponentially in the second half of the 1800s. In the spring of 1854, there were only 12 houses in Minneapolis. Four years later, nearly 6,000 people lived in Minneapolis. That number had increased to over 13,000 by 1870. In 1872, St. Anthony became a part of Minneapolis, and by 1900, the young city had over 200,000 residents.

Burial and memorialization the early U.S. cities

In the early days of American colonialism, most burials took place in churchyards or on private property. But as cities grew and the population of both the living and the dead increased, burial space proved too limited. Many of the nation’s early cemeteries grew in a similar manner to the nation’s early cities—rapidly, and without well-laid designs to accommodate a booming population. Most early urban cemeteries emerged out of necessity rather than careful planning. Many of the U.S.’s first urban cemeteries were privately owned, though used by the public. Often a landowner would allocate a small urban lot for burial, and those without access to their own property or a church graveyard would pay a fee to the owner to be buried on the urban lot.

In the early days of American cities, no one knew just how fast cities would grow—or when they would stop growing. So many of the country’s earliest public cemeteries quickly became overcrowded. Remains were commonly placed on top of one another, graves were not always dug at uniform depths, and records were often inconsistent and incomplete. Many of these early public graveyards were deemed public health risks, and were eventually closed.

Maple Hill Cemetery and Layman’s Cemetery

The story was similar in the young cities of St. Anthony and Minneapolis. Beginning in 1851, the first burials took place at what became St. Anthony’s first public graveyard. The site of Maple Hill Cemetery was originally owned by the Cummings family on land that had been deeded to them by the U.S. Government. Maple Hill Cemetery, though not dedicated until 1857, served as an affordable and peaceful burying place for St. Anthony residents for nearly three decades.

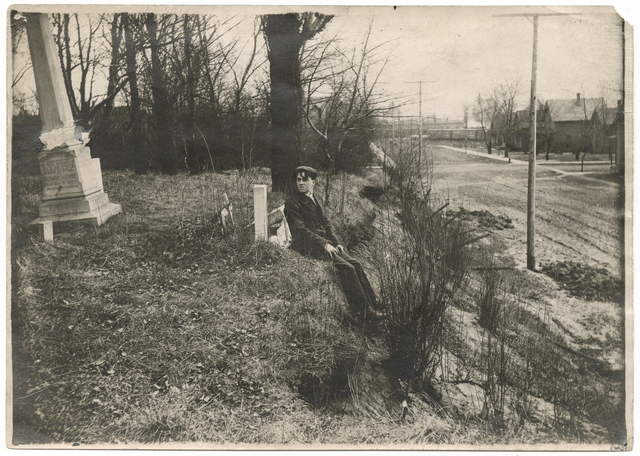

A man sits along the edge of the Maple Hill Cemetery, which had fallen into disrepair by the late 1880s.

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

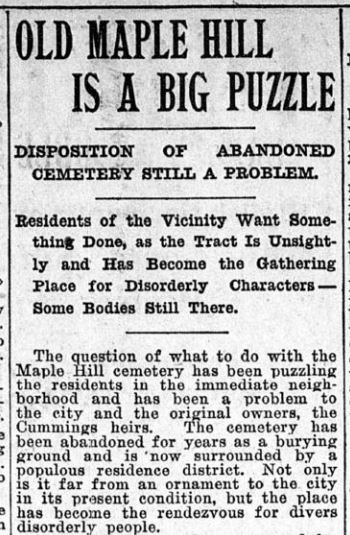

But by the late 1880s, over 5,000 remains had been buried in the small urban burial lot. Broken monuments littered the site, the grounds were unkempt, and records were barely maintained. In 1889, the city closed the cemetery to new burials, but the site remained in ruinous disrepair for nearly two decades. The site became known as a place for vandalism and the malignant games of young children. The ongoing state of the cemetery and the controversy surrounding the mess was covered frequently in the city’s newspapers.

In 1858, Layman’s Cemetery opened on East Lake Street as the town of Minneapolis’s first public graveyard. Now known as Pioneers & Soldiers Cemetery, the site was originally called Layman’s Cemetery, as it was owned by the Layman family. The story was a common one in early U.S. cities: the Laymans had buried a family member on their undeveloped property in 1853. The Laymans later permitted a family friend to bury a loved one on the site. The city lot became a public burial ground that grew with the city. It offered affordable memorial options for many of the city’s early settlers. But as the population of Minneapolis soared, this burial space became quite crowded, too. Recordkeeping was stronger than at Maple Hill Cemetery (and many dedicated historians today are archiving the cemetery’s records), but the space eventually drew negative attention from citizens and the local press for being visually unsettling. The cemetery, which covers 27 acres, had 27,000 burials by the time it was closed by the city in 1919.

(Above right: A 1904 Minneapolis Journal article addresses the disrepair of Maple Hill Cemetery. Source: Minneapolis Journal via Library of Congress.)

Lakewood presents another option

There are many stories as to who had the idea for Lakewood Cemetery. One such story comes from Lakewood founder and “Father of the Parks” Charles Loring. In a letter written to his Park Board colleague George Brackett, Loring told his friend that it was while burying his infant daughter in the already-overcrowded Layman’s Cemetery in 1863 that he had the idea for a grand, beautiful, park-like cemetery in Minneapolis.

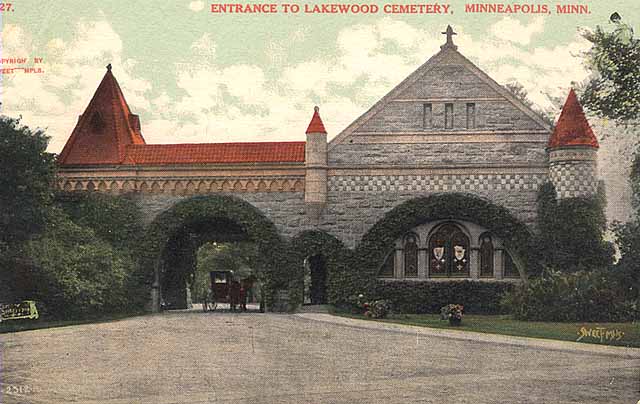

The original entrance to Lakewood Cemetery, as depicted on a 1903 postcard.Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Lakewood was unprecedented for the area, but it wasn’t the first of its kind in the country. Beginning in the mid-1800s, the “Rural Cemetery Movement” was sweeping the eastern United States. The idea emerged out of a middle-class criticism of urbanization. As cities grew rapidly, landscape architects and citizens alike experienced a sort of collective panic—a concern that soon there would be no spaces of natural beauty left in the nation. The bustle of the city was no place to honor the dead, they felt. So they looked to places like Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, whose winding roads and verdant hills were starkly different than the gridded, barren streets of cities. Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts—the first cemetery in the U.S. to be designed in this “Rural Cemetery” style—was opened in 1831 and served as inspiration for many of the country’s park-like cemeteries. So when Lakewood was founded in 1871, it served not only as a cemetery and park, but also as a sort of rejection of rapid urbanization—or at least as a complement to it.

When Lakewood was founded in 1871, it was solidly within this “Rural Cemetery” style. Planners designed such cemeteries to be just outside of the city, but not so far as to be inaccessible to urban dwellers. Such was the case with Lakewood; when the cemetery opened, Minneapolis was bounded on the south by Franklin Avenue.

Lakewood had the distinct advantage of having more space than Minneapolis’s earlier cemeteries (read about the cemetery’s growth over time here). But Lakewood also learned from the recordkeeping and maintenance struggles of the other local cemeteries. Lakewood was plotted out ahead of its opening to accommodate decades of population growth. Grave locations were determined before the time of need, and dug to consistent depths. From its founding, Lakewood was open to all people. Those who wanted to be buried at Lakewood but could not necessarily afford (or did not want) a headstone could be buried without one. Thankfully, Lakewood’s strict recordkeeping means that the names and stories of these individuals live on, too.

When cemeteries close

Many headstones at Lakewood include a death date that predates Lakewood’s opening. That is because many people with the means to do so voluntarily relocated the remains of their loved ones to Lakewood’s scenic grounds when it opened for burials in 1872. Lakewood also received a number of remains from both Maple Hill Cemetery and Layman’s Cemetery when they were closed to new burials.

The issue of cemetery closure was very important to many residents of Minneapolis in the late 1800s and into the 1900s. In the 1920s, many residents organized against the complete closure and repurposing of Layman’s Cemetery. One 1925 editorial asked “Is there no surety for those who inhabit the cities of the dead?” These advocates were successful, and the site remains a frequently visited historic site today.

Volunteers cleaning up Layman’s Cemetery in 1925

Source: Minnesota Historical Society

Though relocation out of Layman’s Cemetery was not mandatory, the city did require that all remains be removed from Maple Hill Cemetery. But their mandate was only somewhat successful; despite having about 5,000 burials when the grounds closed in a report five years later said that only 1,320 bodies and 82 monuments had been moved. The Park Board eventually took control of the site, and in 1916 dedicated Beltrami Park on the site. Today, between rounds of Bocce and a run around the park’s jungle gym, you can still find a few headstones to give you a glimpse of the site’s past history.

One of the few remaining graves at today’s Beltrami Park (formerly Maple Hill Cemetery)Source: Star Tribune