This #EarthMonth on our Facebook page we’ve been honoring some of Minnesota’s environmental heroes who are now laid to rest at Lakewood, giving you a behind-the-scenes look at our greenhouse operation, and keeping you up to date about our changing tree canopy. For nearly 150 years, Lakewood has been building a diverse and beautiful array of trees and bushes. It is even rumored that U of M brought their early horticulture students to Lakewood to take their plant identification tests, because it was the most biodiverse place close to the urban campus.

But in today’s blog, we’ll be talking about a handful of trees on Lakewood’s grounds that are unlike the others. These trees need no water, they do not grow, they do not blow in the breeze. These trees are made of stone, and they are dedicated to the memories of lost loved ones. At first glance one of these unusual, unchanging trees may be mistaken for a real tree, or the trunk of a once grand specimen. If you look closely, “treestones” can be found throughout Lakewood’s grounds.

A treestone at Lakewood Cemetery

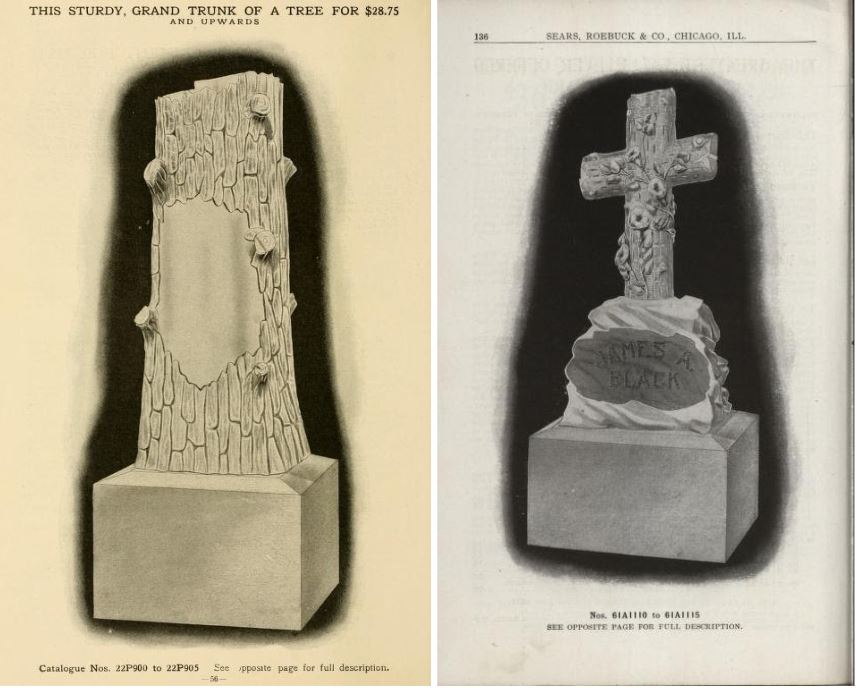

Treestones were so popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s that you could buy one out of the Sears & Roebuck catalog. But to understand their popularity, we’ve got to go back in time.

The City Encroaches on Nature

Treestones’ heyday began in the late 1800s. At this time, natural spaces across the industrializing world were being overtaken by urbanization. Formerly wild spaces were turned into settlements, settlements turned into towns, towns into cities. Cities meant factories, and factories brought pollution along with monotony. The promise of work brought people to the burgeoning urban hubs, and railroads meant a steady supply of goods was constantly coming and going from city to city. Riverfronts were being dammed and developed, and forests were cut down in their entirety.

In this moment of rapid urbanization, there was a sort of collective panic as the US’s natural beauty seemed to be eaten up by our ever-expanding cities. In 1872, Congress established the first nationally-protected park, Yellowstone, “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.” Other national and state parks followed, along with more laws to protect some of the country’s wild spaces from development.

Nature Lives on in Art and Craft

American art and aesthetics began to echo this collective concern. Paintings of idealized natural landscapes dominated the fine art world. Natural images like flowers, branches, and trees cropped up in all sorts of decorative arts—on vases, in furniture, and even on gravestones.

Another treestone at Lakewood

Americans drew their inspiration from England. There, the Industrial Revolution had begun much earlier. And with significantly less land, English artists and thinkers started longing for the pre-urban, pre-capitalist era of craftsmanship. Privileged by the fact that they themselves were usually not the laborers who toiled in the factories, these thinkers and artists pined for the way life was (or how they imagined life was) before cities: the slow pace, the forests, the fields, the rivers. These artists dreamed of that era, and longed to recreate it. They tried to recreate it in their ideology, with one craftsperson creating an object from start to finish, rather than repeating a single task like laborers did on assembly lines. So too did the artists try to recreate that pre-industrial era in their aesthetics; they used simple forms and, at times, motifs pulled directly from nature. In the mid-1800s, England’s Arts and Crafts movement took root.

This artistic movement spread quickly to the urbanized Northeastern US states like New York and Massachusetts. A few cities in the midwest, like Chicago and Minneapolis, picked up on the trend quickly, starting Arts and Crafts societies.

At this time, images of trees and flowers were living on in arts and crafts, even if they were no longer as visible in American cities. Treestones flourished. In a way, these tree-shaped memorials were substitutes for the trees that were being cut down at a rapid pace. Unlike real trees, these stone trees were meant to be permanent.

A small treestone, memorializing a child, at Lakewood

What Fraternal Organizations Had To Do With It

This longing for ever-diminishing natural beauty wasn’t the only reason treestones were so popular in the late 1800s. The second reason may surprise you.

In the late 1800s, the risk of death from disease, environmental toxins, and unregulated workplaces was much higher than it is today. Social Security and other safety nets did not yet exist. On top of all this, life insurance was expensive, available only to the very wealthy.

Fraternal organizations emerged as a solution. Organizations like the Odd Fellows, Knights of Columbus, and Sons of Norway stepped in to provide basic needs when employers and the government did not. These clubs provided social and economic support for working people, offering financial assistance in life and death in exchange for “good” behavior and devotion to the organization. Some fraternal organizations served specific groups of laborers; the Odd Fellows, for example, did odd jobs. Other fraternal organizations were delineated by country of origin or religion. Almost all of them were segregated based on race.

One such fraternal organization was the Modern Woodmen of America. The founder, aptly-named Joseph Cullen Root, saw the organization as “[binding] in one association the Jew and the Gentile, the Catholic and the Protestant, the agnostic and the atheist.” However, like many other fraternal organizations, the Woodmen was only open to white men, and still had a very strong Christian influence; Root got the name “woodmen” from a sermon he heard comparing pioneers to “woodmen” who cleared dense forests to support their families on the frontier. Root was not a carpenter or a lumberman, and his members needn’t be, either.

The Gravestone Promise

Started in Lyons, Iowa, the Modern Woodmen of America were a stronghold in the Midwest. In 1890, Root split with other organization leaders and moved to Omaha to establish the markedly-similar Woodmen of the World. But in this new incarnation, Root offered something unique. “No Woodmen,” his membership materials promised, would “ever rest in an unmarked grave.” It became policy that all Woodmen received a free headstone by dint of membership. And the design of those headstones? They were made to look like trees.

Two early-1900s treestones with prominent Woodmen of the World seals engraved. Located in North Carolina and Ohio. Sources: Pinterest and karenmillerbernett.com

Woodmen’s treestones were customized, and would often have details about the deceased and their family encoded into the carving. A shorter stump may mean a life that ended too soon. Two twisting branches may mean that two members of the family members were reunited in eternal rest. On every Woodmen’s headstone is the Woodmen of the World seal, with the slogan “Dum Tacet, Clamet”—“Though Silent, He Speaks.”

By 1898, the Woodmen had 88,000 members nationwide. Local chapters were called “groves,” many of which had women’s auxiliaries, and all of which were governed by the national “Supreme Forest.” By the early 1900s, there were groves all over Minnesota, sprinkling cemeteries across the state with treestones.

The Trend Continues, then Concludes

The Woodmen weren’t the only people to use treestones, but it’s likely that the Woodmen helped grow the popularity of this type of grave marker. At Lakewood, you’ll find many treestones without the Woodmen of the World seal. Treestones became so popular that by at least 1902 you could purchase tree-shaped headstones from the Sears catalog.

Treestones as advertised in a Sears & Roebuck’s Special Catalogue of Tombstones, Monuments, Tablets and Markers

Marking every Woodman’s grave was a costly endeavor. Eventually the Woodmen started charging members $100 for their personalized headstones. This was far more expensive than Sears’ baseline price of $28.75. (Even this Sears bargain was still upwards of $850 today.)

By the 1920s, treestones started fading in popularity. The Arts and Crafts movement lost steam as the romanticism of pre-capitalist craftsmanship was an increasingly distant memory. The treestone grave program was too costly for the Woodmen to maintain. In the late 1920s, the Great Depression hit fraternal organizations hard, and the 1930s creation of welfare and social security programs made them less necessary. The Woodmen changed course somewhat and morphed into a life insurance company.

Trees of Stone

Today, Lakewood’s treestones remain as a testament to a unique era in our nation’s history: a time when death was so palpable and life insurance was so inaccessible that fraternal organizations—though often tainted with racist and sexist policies—stepped in to meet the needs of their members in life and in death. So too do these treestones commemorate a time when our cities were growing so rapidly that they appeared they might rid us of our natural spaces forever. How fitting that cemeteries, the guardians of these unique and telling memorials, are also places of natural respite in our modern cities. Next time you stroll through Lakewood, be sure to notice the trees.

The Evans family treestones in Lakewood’s Section 11